In his absorbing new book, “

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership,” the

former F.B.I. director James B. Comey calls the

Donald Trump presidency a “forest fire” that is doing serious damage to the country’s norms and traditions.

“This president is unethical

, and untethered to truth and institutional values,” Comey writes. “His leadership is transactional, ego driven and about personal loyalty.”

Decades before he led the F.B.I.’s investigation into whether members of Trump’s campaign colluded with Russia to influence the 2016 election, Comey was a career prosecutor who helped dismantle the Gambino crime family; and he doesn’t hesitate in these pages to draw a direct analogy between the Mafia bosses he helped pack off to prison years ago and the current occupant of the Oval Office.

A February 2017 meeting in the White House with Trump and then chief of staff Reince Priebus left Comey recalling his days as a federal prosecutor facing off against the Mob: “The silent circle of assent. The boss in complete control. The loyalty oaths. The us-versus-them worldview. The lying about all things, large and small, in service to some code of loyalty that put the organization above morality and above the truth.” An earlier visit to Trump Tower in January made Comey think about the New York Mafia social clubs he knew as a Manhattan prosecutor in the 1980s and 1990s — “The Ravenite. The Palma Boys. Café Giardino.”

The central themes that Comey returns to throughout this impassioned book are the toxic consequences of lying; and the corrosive effects of choosing loyalty to an individual over truth and the rule of law. Dishonesty, he writes, was central “to the entire enterprise of organized crime on both sides of the Atlantic,” and so, too, were bullying, peer pressure and groupthink — repellent traits shared by Trump and company, he suggests, and now infecting our culture.

“We are experiencing a dangerous time in our country,” Comey writes, “with a political environment where basic facts are disputed, fundamental truth is questioned, lying is normalized and unethical behavior is ignored, excused or rewarded.”

“

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership” is the first big memoir by a key player in the alarming melodrama that is the Trump administration. Comey, who was abruptly fired by President Trump on May 9, 2017, has worked in three administrations, and his book underscores just how outside presidential norms Trump’s behavior has been — how ignorant he is about his basic duties as president, and how willfully he has flouted the checks and balances that safeguard our democracy, including the essential independence of the judiciary and law enforcement. Comey’s book fleshes out the testimony he gave before the Senate Intelligence Committee in June 2017 with considerable emotional detail, and it showcases its author’s gift for narrative — a skill he clearly honed during his days as United States attorney for the Southern District of New York.

The volume offers little in the way of hard news revelations about investigations by the F.B.I

. or the special counsel Robert S. Mueller III (not unexpectedly, given that such investigations are ongoing and involve classified material), and it lacks the rigorous legal analysis that made Jack Goldsmith’s 2007 book “

The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment Inside the Bush Administration” so incisive about larger dynamics within the Bush administration.

What “

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership" does give readers are some near-cinematic accounts of what Comey was thinking when, as he’s previously said, Trump demanded loyalty from him during a one-on-one dinner at the White House; when Trump pressured him to let go of the investigation into his former national security adviser Michael T. Flynn; and when the president asked what Comey could do to “lift the cloud” of the Russia investigation.

There are some methodical explanations in these pages of the reasoning behind the momentous decisions Comey made regarding Hillary Clinton’s emails during the 2016 campaign — explanations that attest to his nonpartisan and well-intentioned efforts to protect the independence of the F.B.I., but that will leave at least some readers still questioning the judgment calls he made, including the different approaches he took in handling the bureau’s investigation into Clinton (which was made public) and its investigation into the Trump campaign (which was handled with traditional F.B.I. secrecy).

“

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership” also provides sharp sketches of key players in three presidential administrations. Comey draws a scathing portrait of Vice President Dick Cheney’s legal adviser David S. Addington, who spearheaded the arguments of many hard-liners in the George W. Bush White House; Comey describes their point of view: “The war on terrorism justified stretching, if not breaking, the written law.” He depicts Bush national security adviser and later Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice as uninterested in having a detailed policy discussion of interrogation policy and the question of torture. He takes

Barack Obama’s attorney general

Loretta Lynch to task for asking him to refer to the Clinton email case as a “matter,” not an “investigation.” (Comey tartly notes that “the F.B.I. didn’t do ‘matters.’”) And he compares Trump’s attorney general,

Jeff Sessions, to

Alberto R. Gonzales, who served in the same position under Bush, writing that both were “overwhelmed and overmatched by the job,” but “Sessions lacked the kindness Gonzales radiated.”

Comey is what Saul Bellow called a “first-class noticer.” He notices, for instance, “the soft white pouches under” Trump’s “expressionless blue eyes”; coyly observes that the president’s hands are smaller than his own “but did not seem unusually so”; and points out that he never saw Trump laugh — a sign, Comey suspects, of his “deep insecurity, his inability to be vulnerable or to risk himself by appreciating the humor of others, which, on reflection, is really very sad in a leader, and a little scary in a president.”

During his Senate testimony last June, Comey was boy-scout polite (“Lordy, I hope there are tapes”) and somewhat elliptical in explaining why he decided to write detailed memos after each of his encounters with Trump (something he did not do with Presidents Obama or Bush), talking gingerly about “the nature of the person I was interacting with.” Here, however, Comey is blunt about what he thinks of the president, comparing Trump’s demand for loyalty over dinner to “

Sammy the Bull’s Cosa Nostra induction ceremony — with Trump, in the role of the family boss, asking me if I have what it takes to be a ‘made man.’”

Throughout his tenure in the Bush and Obama administrations (he served as deputy attorney general under Bush, and was selected to lead the F.B.I. by Obama in 2013)

, Comey was known for his fierce, go-it-alone independence, and Trump’s behavior catalyzed his worst fears — that the president symbolically wanted the leaders of the law enforcement and national security agencies to come “forward and kiss the great man’s ring.” Comey was feeling unnerved from the moment he met Trump. In his recent book “

Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House,” Michael Wolff wrote that Trump “invariably thought people found him irresistible,” and felt sure, early on, that “he could woo and flatter the F.B.I. director into positive feeling for him, if not outright submission” (in what the reader takes as yet another instance of the president’s inability to process reality or step beyond his own narcissistic delusions).

After he failed to get that submission and the Russia cloud continued to hover, Trump fired Comey; the following day he told Russian officials during a meeting in the Oval Office that firing the F.B.I. director — whom he called “a real nut job” — relieved “great pressure” on him. A week later, the Justice Department appointed Robert Mueller as special counsel overseeing the investigation into ties between the Trump campaign and Russia.

During Comey’s testimony, one senator observed that the often contradictory accounts that the president and former F.B.I. director gave of their one-on-one interactions came down to “Who should we believe?” As a prosecutor, Comey replied, he used to tell juries trying to evaluate a witness that “you can’t cherry-pick” — “You can’t say, ‘I like these things he said, but on this, he’s a dirty, rotten liar.’ You got to take it all together.”

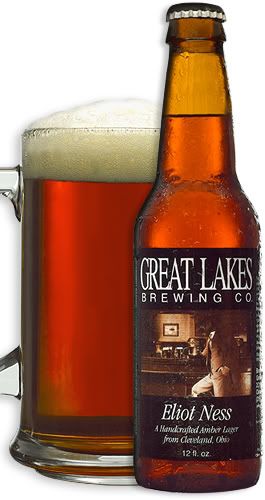

Put the two men’s records, their reputations, even their respective books, side by side, and it’s hard to imagine two more polar opposites than Trump and Comey: They are as antipodean as the untethered, sybaritic

Al Capone and the square,

diligent G-man Eliot Ness in Brian De Palma’s 1987 movie “The Untouchables”; or the vengeful outlaw Frank Miller and Gary Cooper’s stoic, duty-driven marshal Will Kane in Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 classic “High Noon.”

One is an avatar of chaos with autocratic instincts and a resentment of the so-called “deep state” who has waged an assault on the institutions that uphold the Constitution.

The other is a straight-arrow bureaucrat, an apostle of order and the rule of law, whose reputation as a defender of the Constitution was indelibly shaped by his decision, one night in 2004, to rush to the hospital room of his boss, Attorney General John D. Ashcroft, to prevent Bush White House officials from persuading the ailing Ashcroft to reauthorize an N.S.A. surveillance program that members of the Justice Department believed violated the law.

One uses language incoherently on Twitter and in person, emitting a relentless stream of lies, insults, boasts, dog-whistles, divisive appeals to anger and fear, and attacks on institutions, individuals, companies, religions, countries, continents.

The other chooses his words carefully to make sure there is “no fuzz” to what he is saying, someone so self-conscious about his reputation as a person of integrity that when he gave his colleague James R. Clapper, then director of national intelligence, a tie decorated with little martini glasses, he made sure to tell him it was a regift from his brother-in-law.

One is an impulsive, utterly transactional narcissist who, so far in office, The Washington Post calculated, has made an average of six false or misleading claims a day; a winner-take-all bully with a nihilistic view of the world. “Be paranoid,” he advises in one of his own books. In another: “When somebody screws you, screw them back in spades.”

The other wrote his college thesis on religion and politics, embracing Reinhold Niebuhr’s argument that “the Christian must enter the political realm in some way” in order to pursue justice, which keeps “the strong from consuming the weak.”

Until his cover was blown, Comey shared nature photographs on Twitter using the name “Reinhold Niebuhr,” and both his 1982 thesis and this memoir highlight how much Niebuhr’s work resonated with him. They also attest to how a harrowing experience he had as a high school senior — when he and his brother were held captive, in their parents’ New Jersey home, by an armed gunman — must have left him with a lasting awareness of justice and mortality.

Long passages in Comey’s thesis are also devoted to explicating the various sorts of pride that Niebuhr argued could afflict human beings — most notably, moral pride and spiritual pride, which can lead to the sin of self-righteousness. And in “

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership,” Comey provides an inventory of his own flaws, writing that he can be “stubborn, prideful, overconfident and driven by ego.”

Those characteristics can sometimes be seen in Comey’s account of his handling of the Hillary Clinton email investigation, wherein he seems to have felt a moral imperative to address, in a July 2016 press conference, what he described as her “extremely careless” handling of “very sensitive, highly classified information,” even though he went on to conclude that the bureau recommend no charges be filed against her. His announcement marked a departure from precedent in that it was done without coordination with Department of Justice leadership and offered more detail about the bureau’s evaluation of the case than usual.

As for his controversial disclosure on Oct. 28, 2016, 11 days before the election, that the F.B.I. was reviewing more Clinton emails that might be pertinent to its earlier investigation, Comey notes here that he had assumed from media polling that Clinton was going to win. He has repeatedly asked himself, he writes, whether he was influenced by that assumption: “It is entirely possible that, because I was making decisions in an environment where Hillary Clinton was sure to be the next president, my concern about making her an illegitimate president by concealing the restarted investigation bore greater weight than it would have if the election appeared closer or if Donald Trump were ahead in all polls. But I don’t know.”

He adds that he hopes “very much that what we did — what I did — wasn’t a deciding factor in the election.” In testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on May 3, 2017, Comey stated that the very idea that his decisions might have had an impact on the outcome of the presidential race left him feeling “mildly nauseous” — or, as one of his grammatically minded daughters corrected him, “nauseated.”

Trump was reportedly infuriated by Comey’s “nauseous” remark; less than a week later he fired the F.B.I. director — an act regarded by some legal scholars as possible evidence of obstruction of justice, and that quickly led to the appointment of the special counsel Robert Mueller and an even bigger cloud over the White House.

It’s ironic that Comey, who wanted to shield the F.B.I. from politics, should have ended up putting the bureau in the midst of the 2016 election firestorm; just as it’s ironic (and oddly fitting) that a civil servant who has prided himself on being apolitical and independent should find himself reviled by both Trump and Clinton, and thrust into the center of another tipping point in history.

They are ironies that would have been appreciated by Comey’s hero Niebuhr, who wrote as much about the limits, contingencies and unforeseen consequences of human decision-making as he did about the dangers of moral complacency and about the necessity of entering the political arena to try to make a difference.

Reviewed by

Michiko Kakutani.