The aging bosses seated at the defense table in the packed federal courtroom in lower Manhattan look harmless enough to be spectators at a Sunday-after noon boccie game. Anthony (Fat Tony) Salerno, 75, the reputed head of the Genovese crime family, sits aloof and alone, his left eye red and swollen from surgery. White-haired Anthony (Tony Ducks) Corallo, 73, the alleged Lucchese family chief, is casual in a cardigan and sport shirt. Carmine (Junior) Persico, 53, is the balding, baggy-eyed showman of the trio. Elegant in a black pinstripe suit, a crisp white shirt and red tie, the accused Colombo crime boss is acting as his own attorney. "By now I guess you all know my name is Carmine Persico and I'm not a lawyer, I'm a defendant," he humbly told the jury in a thick Brooklyn accent. "Bear with me, please," he said, shuffling through his notes. "I'm a little nervous."

As Persico spoke, three young prosecutors watched, armed with the evidence they hope will show that Junior and his geriatric cohorts are the leaders of a murderous, brutal criminal conspiracy that reaches across the nation. In a dangerous four-year investigation, police and FBI agents had planted bugs around Mafia hangouts and listened to endless hours of tiresome chatter about horses, cars and point spreads while waiting patiently for incriminating comments. They pressured mobsters into becoming informants. They carefully charted the secret family ties, linking odd bits of evidence to reveal criminal patterns. They helped put numerous mafiosi, one by one and in groups, behind bars. But last week, after a half-century in business, the American Mafia itself finally went on trial.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Chertoff, whose bushy mustache could not hide his tender age of 32, addressed the anonymous jurors in calm, methodical tones. Chertoff charged flatly that the Mafia is run by a coordinating Commission and that the eight defendants, representing four of New York City's five nationally powerful Mob families, were either on this crime board or had carried out its racketeering dictates. "What you will see is these men," he said, "these crime leaders, fighting with each other, backstabbing each other, each one trying to get a larger share of the illegal proceeds. You are going to learn that this Commission is dominated by a single principle -- greed. They want more money, and they will do what they have to do to get it."

Across the East River in another federal courthouse in Brooklyn, a jury was being selected for the racketeering trial of the most powerful of all U.S. Mafia families: the Gambinos. Here a younger, more flamboyant crime boss strutted through the courtroom, snapping out orders to subservient henchmen, reveling in his new and lethally acquired notoriety. John Gotti, 45, romanticized in New York City's tabloids as the "Dapper Don" for his tailored $1,800 suits and carefully coiffed hair, has been locked in prison without bail since May, only a few months after he allegedly took control of the Gambino gang following the murder of the previous boss, Paul Castellano.

Gotti, who seemed to personify a vigorous new generation of mobster, may never have a chance to inherit his criminal kingdom. Prosecutor Diane Giacalone, 36, says tapes of conversations between Gotti and his lieutenants, recorded by a trusted Gambino "soldier" turned informant, will provide "direct evidence of John Gotti's role as manager of a gambling enterprise." If convicted, the new crime chief and six lieutenants could be imprisoned for up to 40 years.

The stage has thus been set for the beginning of two of the most significant trials in U.S. Mob history. Finally realizing the full potential of the once slighted Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, federal prosecutors are trying to destroy Mafia families by convincing juries that their very existence is a crime, that their leaders should be imprisoned for long terms and that, eventually, even their ill-gotten gains can be - confiscated. Success in the New York cases, following an unprecedented series of indictments affecting 17 of the 24 Mafia families in the U.S., would hit the Mob where it would hurt most. Out of a formal, oath-taking national Mafia membership of some 1,700, at least half belong to the five New York clans, each of which is larger and more effective than those in any other city.

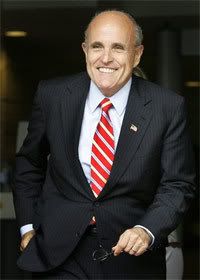

"The Mafia will be crushed," vows Rudolph Giuliani, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, who has been leading the major anti-Mafia crusade and who takes personal affront at the damage done by the Mob to the image of his fellow law-abiding Italian Americans. Declares G. Robert Blakey, a Notre Dame Law School professor who drafted the 1970 RICO law now being used so effectively against organized crime: "It's the twilight of the Mob. It's not dark yet for them, but the sun is going down." Insists John L. Hogan, chief of the FBI's New York office: "We are out to demolish a multiheaded monster and all its tentacles and support systems and followers."

More cynical, or possibly more realistic, law-enforcement authorities doubt that these grand goals can be achieved. But they nonetheless admire the determination and the sophisticated tactics that the current prosecutors are bringing to a battle that has been fought, mostly in vain, ever since the crime-breeding days of Prohibition. Even the doubters concede that the new campaign is off to an impressive start.

From 1981 through last year, federal prosecutors brought 1,025 indictments against 2,554 mafiosi, and have convicted 809 Mafia members or their uninitiated "associates." Many of the remaining cases are still pending. Among all criminal organizations, including such non-Mafia types as motorcycle gangs and Chinese and Latin American drug traffickers, the FBI compiled evidence that last year alone led to 3,803 indictments and 2,960 convictions. At the least, observes the FBI's Hogan, all this legal action means the traditional crime families "are bleeding, they're demoralized."

In Chicago, where the "Outfit" has always been strong, the conviction last January of four top local mobsters for directing the tax-free skimming of cash from two Las Vegas casinos has forced the ailing Anthony Accardo, 80, to return from a comfortable retirement in Palm Springs, Calif., to keep an eye on an inexperienced group of hoods trying to run the rackets. The same skimming case has crippled the mob leadership in Kansas City, Milwaukee and , Cleveland. The New England Mafia, jolted by the convictions in April of Underboss Gennaro Anguilo, 67, and three of his brothers, who operate out of Boston, is described by the FBI as being in a "state of chaos." Of the major Mob clans, only those in Detroit and Newark remain relatively unscathed. But the muscle of organized crime has been most formidable in New York City. Prosecutors have been attacking it with increasing success, but expect to score their biggest win in the so-called Commission case (dubbed Star Chamber by federal investigators). Chertoff and two other young prosecutors handling their first big trial will have to prove that a national Commission made up of the bosses and some underbosses of the major families has been dividing turf and settling disputes among the crime clans ever since New York's ruthless "Lucky" Luciano organized the Commission in 1931. Luciano acted to end the gang warfare that had wiped out at least 40 mobsters in just two days in September of that year. Before that, top gangsters like Salvatore Maranzano had conspired to shoot their way into becoming the capo di tutti capi ("Boss of Bosses"). Maranzano, who had organized New York's Sicilian gangsters into five families, was the first victim of Luciano's new order.

For more than two decades the Mafia managed to keep its board of directors hidden from the outside world, until November 1957, when police staged a celebrated raid on a national mobsters' convention in Apalachin, N.Y. In 1963 former Mafia Soldier Joseph Valachi told a Senate investigating subcommittee all about La Cosa Nostra, the previously secret name under which the brotherhood had operated. After the Mafia had been romanticized in books and movies like The Godfather, some mobsters became brazen about their affairs. In 1983 former New York Boss Joseph Bonanno even published an autobiography about his Mafia years.

Reading that book

,

A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, helped Giuliani realize that the little understood 1970 RICO act could be used against the Mob. "Bonanno has an entire section devoted to the Commission," Giuliani recalled. "It seemed to me that if he could write about it, we could prosecute it."

Bonanno, 82, seems to have had second thoughts about what he triggered. The aged boss has left his Arizona retirement mansion to serve a contempt-of-court sentence in a Springfield, Mo., federal prison rather than give testimony in the Commission trial. The mobster turned author, says one investigator, "is hearing footsteps."

Brought to bay in a courtroom, the Mafia bosses have adopted an unusual defense: rather than fight the Government's efforts to prove the existence of La Cosa Nostra, they admit it. "This case is not about whether there is a Mafia," thundered Defense Attorney Samuel Dawson. "Assume it. Accept it. There is." Nevertheless, he told the jury, "just because a person is a member of the Mafia doesn't mean he has committed the charged crime or even agreed to commit the charged crime." Dawson depicted the Commission as a sort of underworld businessmen's round table that approves new Mafia members and arbitrates disputes. Its purpose, he insisted, is "to avoid -- avoid -- conflict."

Much more sinister conspiracies will be described by Government witnesses in the trial. The prosecutors will contend that the Commission approved three murders and directed loan-sharking and an extensive extortion scheme against the New York City construction industry. The killings involve the 1979 rubout of Bonanno Boss Carmine Galante and two associates. Bonanno Soldier Anthony Indelicato, 30, and alleged current Bonanno Boss Philip (Rusty) Rastelli, 68, are accused of plotting the hit, with the Commission's blessing, to prevent Galante from seizing control of the Gambino family. (Rastelli, already engaged in a separate racketeering case, will face trial later.) The jurors will see a videotape of Indelicato, who is a defendant in the Commission case, being congratulated shortly after the killings by high-ranking Gambino family members at its Ravenite Social Club. "Watch the way they shake hands, watch the way they are congratulating each other," said Prosecutor Chertoff.

The crux of the Government's case, however, is more prosaic than murder. It details a Commission-endorsed scheme to rig bids and allocate contracts to Mob influenced concrete companies in New York City's booming construction industry. Any concrete-pouring contract worth more than $2 million was controlled by the Mob, according to the indictment, and the gangsters decided who should submit the lowest bids. Any company that disobeyed the bidding rules might find itself with unexpected labor problems, and its sources of cement might dry up. The club dues, actually a form of extortion, amounted to $1.8 million between 1981 and 1984. The Mob also demanded a 2% cut of the value of the contracts it controlled.

The key defendant on this charge is Ralph Scopo, 57, a soldier in the Colombo family, and just as importantly, the president of the Cement and Concrete Workers District Council before he was indicted. Scopo is accused of accepting many of the payoffs from the participating concrete firms. Scopo's lawyer admits the union leader took payoffs, but he and the other attorneys deny it was part of a broader extortion scheme. Since the Mafia leaders own some of the construction companies, said Dawson, the Government was claiming "that these men extort themselves."

Although the Commission trial involves four of New York's five Mob families, a more recent murder plot has prevented the Gambino family from being represented. Former Gambino Boss Paul Castellano and Underboss Aniello Dellacroce had been indicted. But Dellacroce, 71, died last Dec. 2 of cancer. Just 14 days later Castellano, 72, and Thomas Bilotti, 45, his trusted bodyguard and the apparent choice to succeed Dellacroce, were the victims of yet another sensational Mob hit as they walked, unarmed, from their car toward a mid-Manhattan steak house.

Law-enforcement agents are convinced that Gotti, a protege of Dellacroce's, helped plot the Castellano and Bilotti slayings to ensure his own rise to the top of the Gambino clan. No one, however, has been charged with those slayings. The Castellano hit may not come up at the racketeering trial of Gotti, his brother Eugene and four Gambino associates. But two other murders and a conspiracy to commit murder are among 15 crimes that the Government says formed a pattern of participation in a criminal enterprise. The defendants are also accused of planning two armored-car robberies, other hijackings and gambling, and conspiracy to commit extortion.

The major evidence in the Gotti case was provided through a bugging scheme worthy of a James Bond movie. In 1984 Gambino Soldier Dominick Lofaro, 56, was arrested in upstate New York on heroin charges. Facing a 20-year sentence, he agreed to become a Government informant. Investigators wired him with a tiny microphone taped to his chest and a miniature cassette recorder, no bigger than two packs of gum, that fitted into the small of his back without producing a bulge. Equipped with a magnetic switch on a cigarette lighter to activate the recorder, Lofaro coolly discussed Gambino family affairs with the unsuspecting Gotti brothers. Afterward he placed the tapes inside folded copies of the New York Times business section and dropped them in a preselected trash bin. Lofaro provided the Government with more than 50 tapes over two years. Says one admiring investigator: "You can't help wondering how many sleepless nights he spent knowing that if caught he would get a slow cutting job by a knife expert."

The increasing use of wiretaps and tapes, says another investigator, is "like opening a Pandora's box of the Mafia's top secrets and letting them all hang out in the open." Both top Mafia trials will depend heavily on tapes as evidence, as have numerous RICO cases around the country. The FBI's bugging has increased sharply, from just 90 court-approved requests in 1982 to more than 150 in each of the past two years. The various investigating agencies, including state and local police, have found novel places to hide their bugs: in a Perrier bottle, a stuffed toy, a pair of binoculars, shoes, an electric blanket, a horse's saddle. Agents even admit to dropping snooping devices into a confessional at a Roman Catholic church frequented by mobsters, as well as a church candlestick holder and a church men's room. All this, agents insist, was done with court permission.

An agent posing as a street hot-dog vendor in a Mafia neighborhood in New York City discovered which public telephone was being used by gangsters to call sources in Sicily about heroin shipments. The phone was quickly tapped, and the evidence it provided has been used in the ongoing "pizza connection" heroin trial against U.S. and Sicilian mobsters.

The agents were even able to slip a bug into "Big Paul" Castellano's house on Staten Island some two years before he was murdered. Ironically, they heard Castellano apparently complaining about Sparks Steak House, the site of his death. "You know who's really busy making a real fortune?" Big Paul asked a crony. "(Expletive) Sparks. I don't get 5 cents when I go in there. I want you to know that. Shut the house this way if I don't get 5 cents." In Mob lingo, authorities speculate, he seemed to be warning that the restaurant would be closed if it did not start paying extortion money to the Gambino family.

In Boston, FBI agents acquired details on the interiors of two Mafia apartments in the city's North End. With court approval, agents picked the locks early in the morning and planted bugs that produced 800 hours of recordings. The monitoring agents learned fascinating tidbits about Mob mores. Ilario Zannino was heard explaining how dangerous it is to kill just one member of a gang. "If you're clipping people," he said, "I always say, make sure you clip the people around him first. Get them together, 'cause everybody's got a friend. He could be the dirtiest (expletive) in the world, but someone that likes this guy, that's the guy that sneaks you." They heard Zannino and John Cincotti complaining about a competing Irish gang of hoods. Said Cincotti: "They don't have the scruples that we have." Zannino agreed. "You know how I knew they weren't Italiano? When they bombed the (expletive) house. We don't do that."

A major break in the Commission case came on a rainy night in March 1983 when two agents of the New York State Organized Crime Task Force carried out a well-rehearsed planting of a tiny radio transmitter in a 1982 black Jaguar used by "Tony Ducks" Corallo. In a parking lot outside a restaurant in Huntington, N.Y., on Long Island, one agent carefully opened a door, pressing the switch that would otherwise turn on the interior lights. Another helped him spread a plastic sheath over the seats so that rain would not spot the upholstery. With a stopwatch at hand, they quickly removed the dashboard, installed the bug, replaced the dash and closed the car door. The operation took 15 minutes.

For four months the bug transmitted intimate Mob conversations between the Lucchese boss and his driver, Salvatore Avellino, to agents trailing discreetly in various "chase cars," which rebroadcast the signals to a recording van. "It was the most significant information regarding the structure and function of the Commission that has ever been obtained from electronic surveillance," declared Ronald Goldstock, chief of the Organized Crime Task Force. After building his own case against the Lucchese family for a local carting-industry racket, Goldstock alerted Giuliani to the broader implications of using the evidence to attack the Mob's controlling Commission.

Where federal agents and local police once distrusted one another and often collided in their organized-crime investigations, a new spirit of cooperation is proving effective. In New York, state investigators have been invaluable to the FBI in probing the Mob, and some 150 New York City police are assigned full time to the New York FBI office.

The current wave of Mob trials has benefited as well from the number of former gangsters who have proved willing to violate the Mafia's centuries-old tradition of omerta (silence) and provide evidence against their former partners. Racket victims are less fearful than before of testifying. Nationwide, says Giuliani, "we've got more than 100 people who have testified against Mafia guys." To be sure, many witnesses are criminals facing long sentences; they have a strong self-interest in currying favor with prosecutors.

That is a point that the defense lawyers attack forcefully. "I can't tell a witness in jail to come and testify for me and I'll give him his freedom," Persico told the Commission jury. "The Government can do that. They're powerful people . . . Not me." Persico, a high school graduate who learned legal tactics working on appeals during some 14 years behind bars, is described by his longtime attorney, Stanley Meyer, as "the most intelligent fellow I have ever met in any walk of life." His unusual self-defense role also gives him a chance to come across as an unsinister personality to jurors. Persico's strategy, says one court veteran, "is brilliant, if it works." But he runs a risk: his questions must not convey knowledge of events that an innocent person would not possess.

The Commission trial is not expected to produce a turncoat as high ranking as Cleveland Underboss Angelo Lonardo, the top U.S. mobster to sing so far. He learned how to be a turncoat the hard way. Charged with leading a drug ring, Lonardo was convicted after a lesser hood, Carmen Zagaria, testified about the inner workings of the Cleveland Mob. Zagaria described how the bodies of hit victims were chopped up and tossed into Lake Erie. Lonardo, who wanted to avoid a life sentence, then helped prosecutors break the Las Vegas skimming case.

John Gotti is haunted by the deception of Wilfred ("Willie Boy") Johnson, a Gambino-family associate. Caught carrying $50,000 in a paper bag in 1981, Johnson invited New York City detectives to help themselves to the cash. They charged him with bribery. After that Johnson, who hung out at Gotti's Bergen Hunt and Fish Club, kept the cops posted on how the rising star was progressing. He also suggested where bugs might be placed.

The most loquacious turncoat may be James Frattiano, 72, once the acting boss of a Los Angeles crime family. He not only confessed publicly to killing eleven people but also wrote a revealing book, The Last Mafioso, and has taken his story on the road, testifying at numerous trials. All this public testimony means that the Mafia is losing what Floyd Clark, assistant FBI director in charge of criminal investigations, calls a "tremendous asset: fear and intimidation. That shield is being removed."

The willingness of some hoodlums and victims to defy the Mob is partly due to the existence of the Federal Witness Security Program, which since it started in 1970 has helped 4,889 people move to different locations and acquire new identities and jobs. At a cost to the Government of about $100,000 for each protected person, the program has produced convictions in 78% of the cases in which such witnesses were used. For some former gangsters, however, a conventional life in a small town turns out to be a drag. They run up fresh debts and sometimes revert to crime.

A more significant reason for the breakdown in Mob discipline is that the new generation of family members is not as dedicated to the old Sicilian-bred mores. Some mafiosi may have been in trouble with their families already. "Often, they're going to be killed if they don't go to the Government," says Barbara Jones, an attorney in Giuliani's office. Others feel that a long prison sentence is too stiff a price to pay for family loyalty. The younger mafiosi, explains one Justice Department source, "are much more Americanized than the old boys. They enjoy the good life. There's more than a bit of yuppie in them." Contends RICO Author Blakey: "The younger members are a little more crass, a little less honest and respectful, a little more individualistic and easier to flip."

The combination of prosecutorial pressure and the slipping of family ties may be feeding upon itself, creating further disunity and casting a shadow over the Mob's future. Certainly, when the old-timers go to prison for long terms, they lose their grip on their families, particularly if ambitious successors do not expect them to return. Younger bosses serving light sentences can keep operating from prison, dispatching orders through their lawyers and visiting relatives. They may use other, less watched inmates to send messages. Prison mail is rarely read by censors.

Still, the convicted dons run risks. The prison pay phones may be legally tapped. When the feds learned that the late Kansas City boss Nick Civella was directing killings from Leavenworth prison in Kansas, they bugged the visitors' room and indicted him for new crimes. But can prison bars really crush the Mob? Giuliani contends that as the Italian-American community has grown away from its immigrant beginnings, La Cosa Nostra has been losing its original base of operations and recruits. Pointing to the relatively small number of "made" Mafia members, Giuliani says, "We are fighting an enemy that has definable limits in terms of manpower. They cannot replenish themselves the way they used to in the '20s, '30s and '40s." The Mafia seems aware of the problem: U.S. mobsters have been recruiting hundreds of loyal southern Italian immigrants to run family- owned pizza parlors, help with the heroin traffic, and strengthen the ranks. Experts point out that the Mafia remains a wealthy organization that collected at least $26 billion last year. The Mob has deep roots in unions and labor- intensive industries such as building construction, transportation, restaurants and clothing. In many industries, says Ray Maria, the Labor Department's deputy inspector general, "the Mob controls your labor costs and determines whether you are reputable and profitable."

Repeated prosecutions alone will not put the organization out of its deadly business. Veteran observers of the Mob recall the prediction of the imminent demise of the Chicago Outfit in 1943 when its seven highest hoods were convicted of shaking down Hollywood movie producers. The bell of doom seemed to be tolling nationwide in 1963 when Joseph Valachi's disclosures set off an FBI bugging war against the families. In 1975 the most successful labor racketeering prosecution in U.S. history was supposed to have cleaned up the terror-ridden East Coast waterfront from Miami to New York. None of those highly publicized events had lasting impact.

Still, today's zealous prosecutors have a new tool that gives them a fighting chance to take the organization out of organized crime, if not actually to rub out the Mob. The same RICO law that allows prosecutions against criminal organizations also provides for civil action to seize their assets, from cash to cars and hangouts. A prime example of this technique was the action taken in 1981 against Teamsters Local 560 after it was shown to have been dominated by New York's Genovese family. A civil suit led to the discharge of the local's officers. The union was placed under a court- appointed trustee until free elections could be held. While such suits have been attempted against organized-crime figures only ten times, top Justice Department officials concede they have underestimated the leverage the law can give them. They vow to follow up the convictions they have been winning with civil suits against the family leaders.

The crusading Giuliani admits that the old practice of locking up a capo or two "just helped to speed the succession along." But by striking at all levels of the Mob families and then "peeling away their empires," Giuliani insists, "it is not an unrealistic goal to crush them." Perhaps. But first there are two new and potentially historic courtroom battles to be fought. For the Mob, and for an optimistic new generation of federal crime fighters, it is High Noon in New York.

Thanks to

Ed Magnuson

, the longtime boss of the Colombo crime family, died at age 85, the Daily News has learned.

, the longtime boss of the Colombo crime family, died at age 85, the Daily News has learned. in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss