Prosecutors appear to be treating their investigation of former President Donald Trump's business empire as if it were a mafia family, according to several reports out this week.

Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance is likely considering criminal charges centered around the idea that the Trump Organization is a "corrupt enterprise" under a New York state racketeering statute resembling the federal RICO law — an abbreviation for the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, which was passed in 1970 to crack down on pervasive organized crime — several legal experts and former prosecutors told Politico.

"No self-respecting state white-collar prosecutor would forgo considering the enterprise corruption charge," longtime New York City defense attorney Robert Anello said. "I'm sure they're thinking about that."

The law, known colloquially as "little RICO," kicks in if prosecutors can establish that an organization or business has committed at least three separate crimes — a "pattern of criminal behavior," in legal parlance. A sentence under the statute can result in up to 25 years in prison — with a mandatory minimum of one year.

Vance has even hired a veteran mob prosecutor and expert in white-collar crime, Mark Pomerantz, to bolster his team, the New York Times reported in February.

Trump himself has a long history with several prominent New York City mob families — building his signature Trump Tower in Manhattan with help from a concrete company run by Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno and Paul Castellano, who at the time were bosses of the Genovese and Gambino families, Business Insider reported.

And just like in the investigations that put Salerno and Castellano behind bars, it appears prosecutors are hoping to rely on the testimony of "family" members like Trump Organization CFO Alan Weisselberg, one of the company's longest-tenured employees. His former daughter-in-law, Jennifer Weisselberg, is cooperating with Vance's investigation and says she believes her ex-husband's father will flip on Trump due to his age and aversion to spending any time in prison.

New York Attorney General Letitia James, who recently agreed to join forces with Vance on her separate investigation of Trump's business dealings, has also forced Trump's son, Eric, to sit for a deposition interview, according to the New York Times. But the decision to pursue racketeering charges carries its own risks, and many legal experts say prosecutors are better off seeking straightforward indictments on specific crimes that are easier to litigate.

"Why overcharge and complicate something that could be fairly simple?" Jeremy Saland, a former prosecutor in the Manhattan DA's office, told Politico. "Why muddy up the water? Why give a defense attorney something that could confuse a jury and be able to crow that they beat a charge in a motion to dismiss?"

Trump has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing, and blasted the investigations as politically inspired "witch hunts."

Thanks to Brett Bachman.

Get the latest breaking current news and explore our Historic Archive of articles focusing on The Mafia, Organized Crime, The Mob and Mobsters, Gangs and Gangsters, Political Corruption, True Crime, and the Legal System at TheChicagoSyndicate.com

Showing posts with label Paul Castellano. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Paul Castellano. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 01, 2021

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Mafia Summit: J. Edgar Hoover, the Kennedy Brothers, and the Meeting That Unmasked the Mob

Mafia Summit: J. Edgar Hoover, the Kennedy Brothers, and the Meeting That Unmasked the Mob, is the true story of how a small-town lawman in upstate New York busted a Cosa Nostra conference in 1957 , exposing the Mafia to America

, exposing the Mafia to America

In a small village in upstate New York, mob bosses from all over the country—Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, Joe Bonanno, Joe Profaci, Cuba boss Santo Trafficante, and future Gambino boss Paul Castellano—were nabbed by Sergeant Edgar D. Croswell as they gathered to sort out a bloody war of succession.

For years, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had adamantly denied the existence of the Mafia, but young Robert Kennedy immediately recognized the shattering importance of the Appalachian summit. As attorney general when his brother JFK became president, Bobby embarked on a campaign to break the spine of the mob, engaging in a furious turf battle with the powerful Hoover.

Detailing mob killings, the early days of the heroin trade, and the crusade to loosen the hold of organized crime, fans of Gus Russo and Luc Sante will find themselves captured by this momentous story. Reavill scintillatingly recounts the beginning of the end for the Mafia in America and how it began with a good man in the right place at the right time.

, exposing the Mafia to America

, exposing the Mafia to America

In a small village in upstate New York, mob bosses from all over the country—Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, Joe Bonanno, Joe Profaci, Cuba boss Santo Trafficante, and future Gambino boss Paul Castellano—were nabbed by Sergeant Edgar D. Croswell as they gathered to sort out a bloody war of succession.

For years, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had adamantly denied the existence of the Mafia, but young Robert Kennedy immediately recognized the shattering importance of the Appalachian summit. As attorney general when his brother JFK became president, Bobby embarked on a campaign to break the spine of the mob, engaging in a furious turf battle with the powerful Hoover.

Detailing mob killings, the early days of the heroin trade, and the crusade to loosen the hold of organized crime, fans of Gus Russo and Luc Sante will find themselves captured by this momentous story. Reavill scintillatingly recounts the beginning of the end for the Mafia in America and how it began with a good man in the right place at the right time.

Related Headlines

Books,

Carlo Gambino,

J. Edgar Hoover,

JFK,

Joe Bonanno,

Joe Profaci,

Paul Castellano,

RFK,

Santo Trafficante,

Vito Genovese

No comments:

Monday, March 25, 2019

Anthony Comello, Suspect in Murder of Mafia Boss Frank Cali, Looking at Death Penalty from the Mob

It’s Mob Justice 101, and there are no appeals: The unsanctioned killing of a Mafia boss carries the death penalty.

The longstanding organized crime maxim is bad news for the life expectancy of Anthony Comello, the suspect jailed in the Staten Island shooting death of Gambino family head Frank (Frankie Boy) Cali.

“He must know his life is worth nothing,” said one-time Bonanno family associate Joe Barone. “He doesn’t have a chance in hell. It’s a matter of time. Even if the wiseguys don’t get him, he’ll get whacked by somebody looking to make a name.”

Comello, 24, remains in protective custody in a Jersey Shore jail, held without bail in the March 13 slaying of Cali outside his Staten Island home. Cali was shot 10 times in what initially appeared to be the first hit of a sitting New York mob boss since the execution of his long-ago Gambino predecessor Paul Castellano.

Veteran mob chronicler Selwyn Raab , author of the seminal Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires,” said retribution might not occur instantly. But Comello’s best-case scenario is a life spent looking over his shoulder. “Very simply, the old rules in the Mafia are you don’t let somebody get away with something like this," said Raab. “As long as the Mafia exists, he’s in danger. And it’s not just the Gambinos — anybody from any of the other families could go after him. If they get an opportunity to knock him off, they will."

, author of the seminal Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires,” said retribution might not occur instantly. But Comello’s best-case scenario is a life spent looking over his shoulder. “Very simply, the old rules in the Mafia are you don’t let somebody get away with something like this," said Raab. “As long as the Mafia exists, he’s in danger. And it’s not just the Gambinos — anybody from any of the other families could go after him. If they get an opportunity to knock him off, they will."

Even the Cali family’s initial refusal to share security video with the NYPD was consistent with the mob’s approach to crime family business.

“That’s a big message: We’ll take care of this ourselves,” said Barone, who became an FBI informant.

The Castellano murder, orchestrated by his Gambino family successor John Gotti in December 1985, led to a trio of retaliatory killings sanctioned by Genovese family boss Vincent (The Chin) Gigante.

The Greenwich Village-based Gigante was outraged that Gotti ordered the hit without his approval. The murders were spread across five years and meant to culminate with the killing of Gotti, who instead died behind bars after his underlings were picked off.

The mob doesn’t always get its man. Notorious informants like Gotti’s right-hand man Sammy (The Bull) Gravano and Henry Hill of “Goodfellas” fame bolted from the Witness Protection Program and survived for decades.

Gravano, whose testimony convicted Gotti and 36 other gangsters, walked out of an Arizona prison one year ago after serving nearly 20 years for overseeing an ecstasy ring. Hill died of natural causes in June 2012 at the age of 69, although not all are as fortunate.

Lucchese family associate Bruno Facciola was executed in August 1990, with a dead canary stuffed in his mouth as a sign that he was an informer — and a warning to other mobsters.

Thanks to Larry McShane.

The longstanding organized crime maxim is bad news for the life expectancy of Anthony Comello, the suspect jailed in the Staten Island shooting death of Gambino family head Frank (Frankie Boy) Cali.

“He must know his life is worth nothing,” said one-time Bonanno family associate Joe Barone. “He doesn’t have a chance in hell. It’s a matter of time. Even if the wiseguys don’t get him, he’ll get whacked by somebody looking to make a name.”

Comello, 24, remains in protective custody in a Jersey Shore jail, held without bail in the March 13 slaying of Cali outside his Staten Island home. Cali was shot 10 times in what initially appeared to be the first hit of a sitting New York mob boss since the execution of his long-ago Gambino predecessor Paul Castellano.

Veteran mob chronicler Selwyn Raab

, author of the seminal Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires,” said retribution might not occur instantly. But Comello’s best-case scenario is a life spent looking over his shoulder. “Very simply, the old rules in the Mafia are you don’t let somebody get away with something like this," said Raab. “As long as the Mafia exists, he’s in danger. And it’s not just the Gambinos — anybody from any of the other families could go after him. If they get an opportunity to knock him off, they will."

, author of the seminal Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires,” said retribution might not occur instantly. But Comello’s best-case scenario is a life spent looking over his shoulder. “Very simply, the old rules in the Mafia are you don’t let somebody get away with something like this," said Raab. “As long as the Mafia exists, he’s in danger. And it’s not just the Gambinos — anybody from any of the other families could go after him. If they get an opportunity to knock him off, they will."Even the Cali family’s initial refusal to share security video with the NYPD was consistent with the mob’s approach to crime family business.

“That’s a big message: We’ll take care of this ourselves,” said Barone, who became an FBI informant.

The Castellano murder, orchestrated by his Gambino family successor John Gotti in December 1985, led to a trio of retaliatory killings sanctioned by Genovese family boss Vincent (The Chin) Gigante.

The Greenwich Village-based Gigante was outraged that Gotti ordered the hit without his approval. The murders were spread across five years and meant to culminate with the killing of Gotti, who instead died behind bars after his underlings were picked off.

- Victim No. 1, dispatched by a Brooklyn car bomb, was Gambino underboss Frank DeCicco in April 1987.

- Castellano shooter Eddie Lino became Victim No. 2 after a November 1990 traffic stop on the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn. Unfortunately for him, the officers involved were the infamous “Mafia Cops” — who killed the mob gunman for a $75,000 fee.

- And finally, Victim No. 3: Bobby Borriello, the driver and bodyguard for the Dapper Don, murdered April 13, 1991, in the driveway of his Brooklyn home.

The mob doesn’t always get its man. Notorious informants like Gotti’s right-hand man Sammy (The Bull) Gravano and Henry Hill of “Goodfellas” fame bolted from the Witness Protection Program and survived for decades.

Gravano, whose testimony convicted Gotti and 36 other gangsters, walked out of an Arizona prison one year ago after serving nearly 20 years for overseeing an ecstasy ring. Hill died of natural causes in June 2012 at the age of 69, although not all are as fortunate.

Lucchese family associate Bruno Facciola was executed in August 1990, with a dead canary stuffed in his mouth as a sign that he was an informer — and a warning to other mobsters.

Thanks to Larry McShane.

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

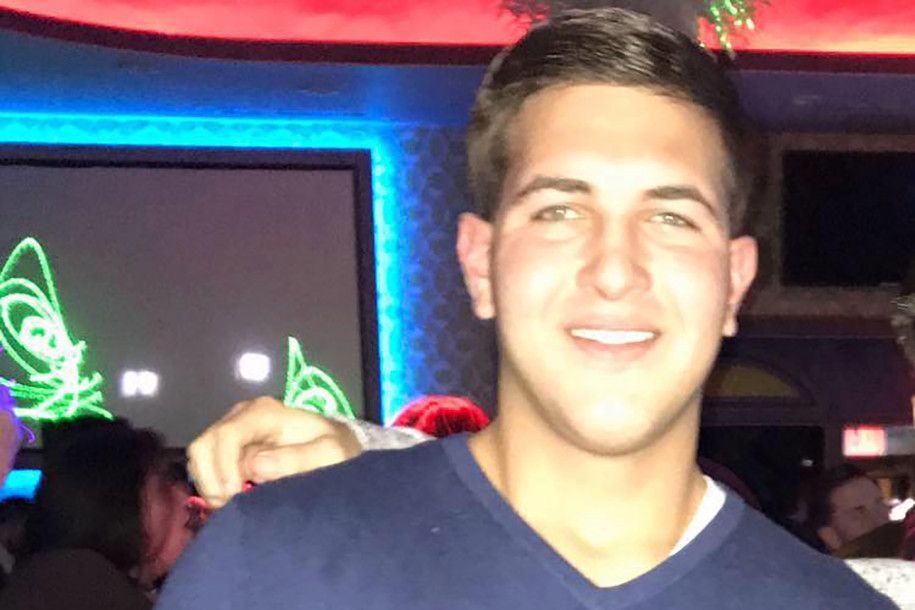

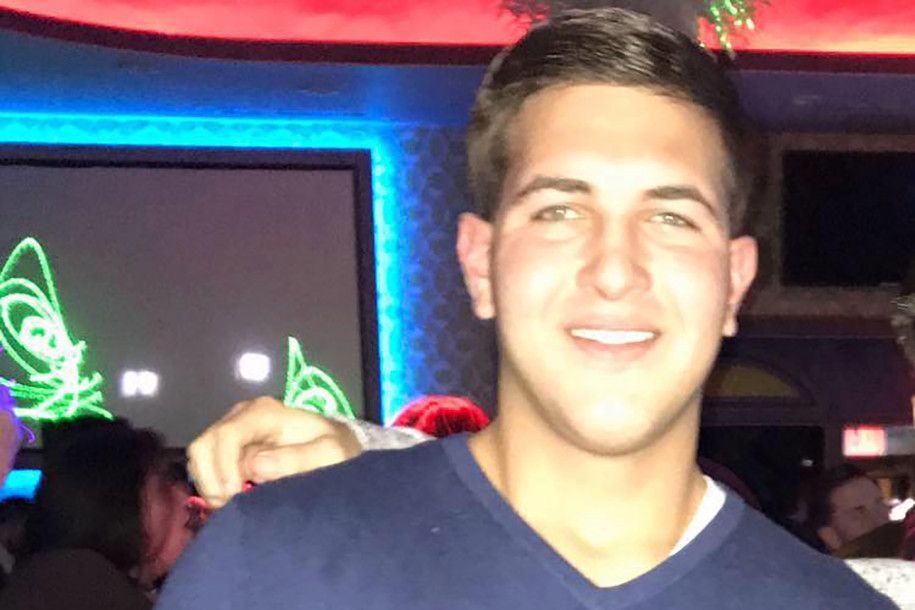

Mob Boss Killer Anthony Comello Shows Love of Trump with Pen Markings of #MAGA Forever and Additional Patriot Slogans

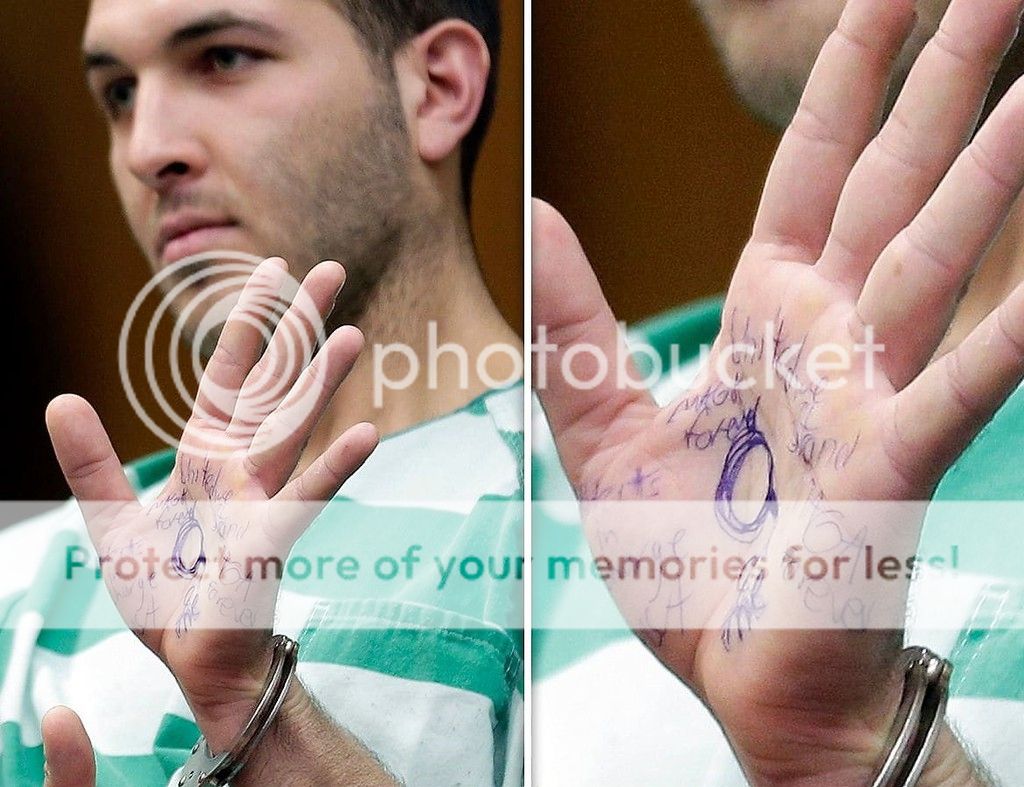

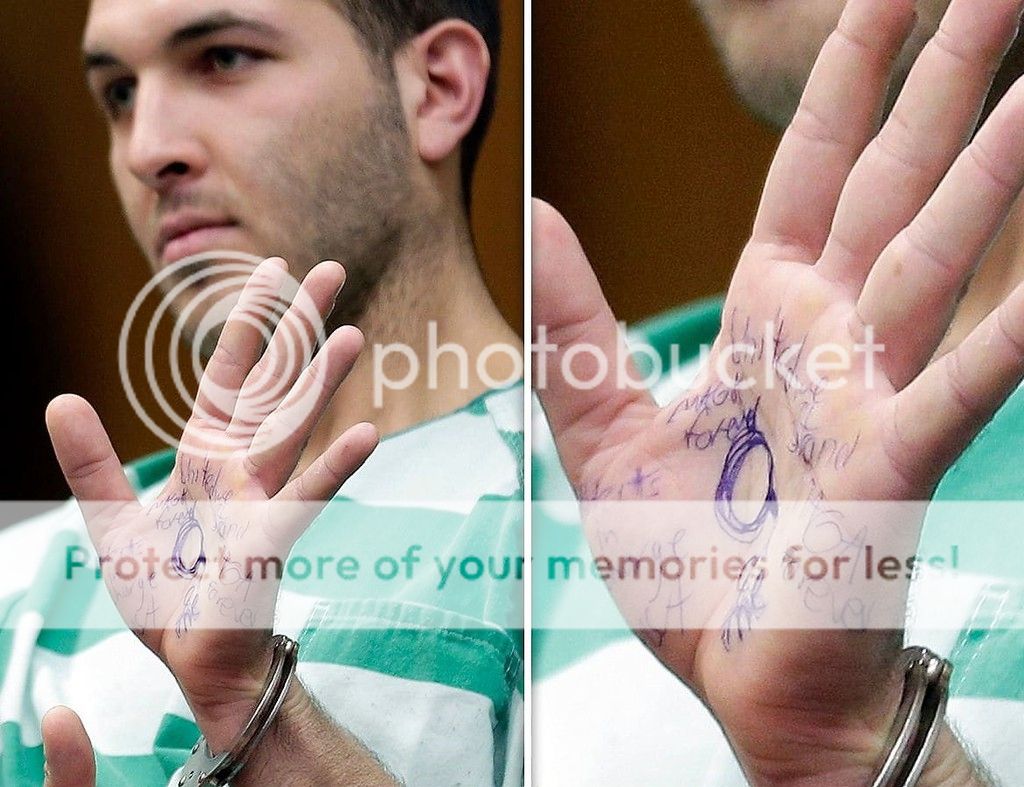

The man charged with killing the reputed boss of the Gambino crime family wrote pro-Donald Trump slogans on his hand and flashed them to journalists before a court hearing Monday.

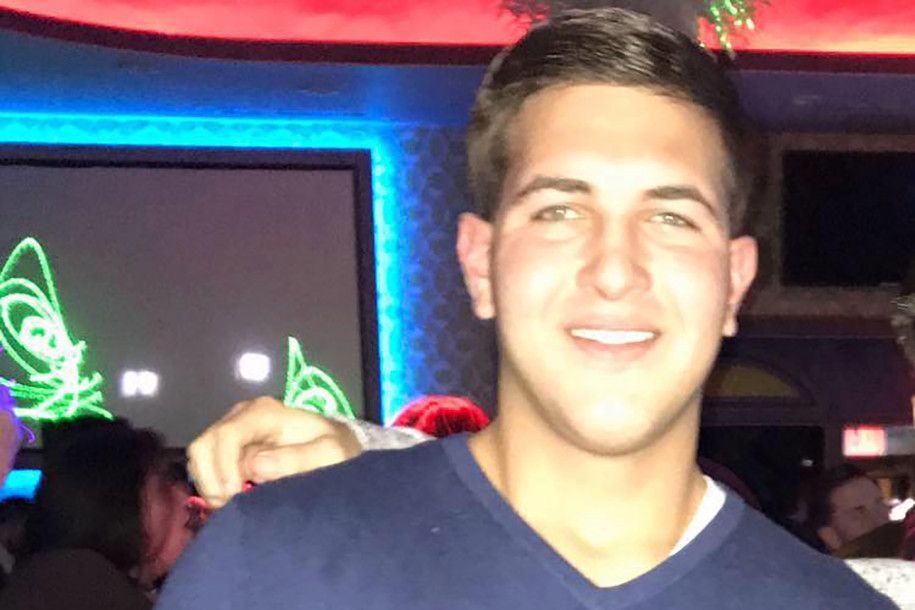

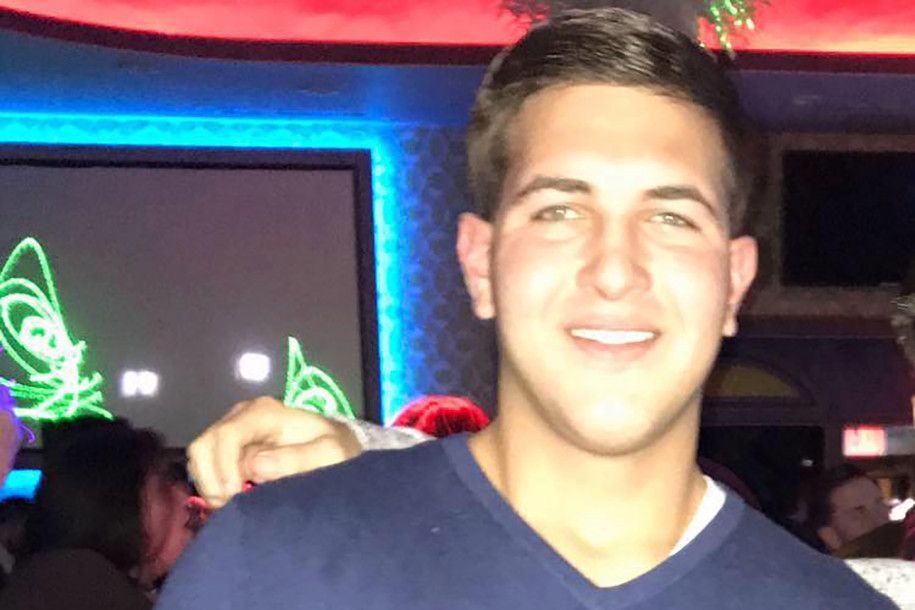

Anthony Comello, 24, was arrested Saturday in New Jersey in the death of Francesco "Franky Boy" Cali last week in front of his Staten Island home.

While waiting for a court hearing to begin in Toms River, New Jersey, in which he agreed to be extradited to New York, Comello held up his left hand.

On it were scrawled pro-Trump slogans including "MAGA Forever," an abbreviation of Trump's campaign slogan "Make America Great Again." It also read "United We Stand MAGA" and "Patriots In Charge." In the center of his palm he had drawn a large circle. It was not immediately clear why he had done so.

Comello's lawyer, Brian Neary, would not discuss the writing on his client's hand, nor would he say whether Comello maintains his innocence. Asked by reporters after the hearing what was on Comello's hand, Neary replied, "Handcuffs."

He referred all other questions to Comello's Manhattan lawyer, Robert Gottlieb, who said in an emailed statement his client has been placed in protective custody due to "serious threats" that had been made against him, but gave no details of them. Ocean County officials could not immediately be reached after hours on Monday.

"Mr. Comello's family and friends simply cannot believe what they have been told," Gottlieb said. "There is something very wrong here and we will get to the truth about what happened as quickly as possible."

The statement did not address the writing on Comello's hand, and a lawyer from Gottlieb's firm declined to comment further Monday evening.

Comello sat with a slight smile in the jury box of the courtroom Monday afternoon as dozens of reporters and photographers filed into the room. When they were in place, Comello held up his left hand to display the writings as the click and whirr of camera lenses filled the room with sound.

During the hearing, Comello did not speak other than to say, "Yes, sir" to the judge to respond to several procedural questions.

Cali, 53, was shot to death last Wednesday by a gunman who may have crashed his truck into Cali's car to lure him outside. Police said Cali was shot 10 times.

Federal prosecutors referred to Cali in court filings in 2014 as the underboss of the Mafia's Gambino family, once one of the country's most powerful crime organizations. News accounts since 2015 said Cali had ascended to the top spot, though he was never charged with leading the gang. His only mob-related conviction came a decade ago, when he was sentenced to 16 months in prison in an extortion scheme involving a failed attempt to build a NASCAR track on Staten Island. He was released in 2009 and hasn't been in legal trouble since then.

Police have not yet said whether they believe Cali's murder was a mob hit or whether he was killed for some other motive.

The last Mafia boss to be rubbed out in New York City was Gambino don "Big Paul" Castellano, who was assassinated in 1985.

Anthony Comello, 24, was arrested Saturday in New Jersey in the death of Francesco "Franky Boy" Cali last week in front of his Staten Island home.

While waiting for a court hearing to begin in Toms River, New Jersey, in which he agreed to be extradited to New York, Comello held up his left hand.

On it were scrawled pro-Trump slogans including "MAGA Forever," an abbreviation of Trump's campaign slogan "Make America Great Again." It also read "United We Stand MAGA" and "Patriots In Charge." In the center of his palm he had drawn a large circle. It was not immediately clear why he had done so.

Comello's lawyer, Brian Neary, would not discuss the writing on his client's hand, nor would he say whether Comello maintains his innocence. Asked by reporters after the hearing what was on Comello's hand, Neary replied, "Handcuffs."

He referred all other questions to Comello's Manhattan lawyer, Robert Gottlieb, who said in an emailed statement his client has been placed in protective custody due to "serious threats" that had been made against him, but gave no details of them. Ocean County officials could not immediately be reached after hours on Monday.

"Mr. Comello's family and friends simply cannot believe what they have been told," Gottlieb said. "There is something very wrong here and we will get to the truth about what happened as quickly as possible."

The statement did not address the writing on Comello's hand, and a lawyer from Gottlieb's firm declined to comment further Monday evening.

Comello sat with a slight smile in the jury box of the courtroom Monday afternoon as dozens of reporters and photographers filed into the room. When they were in place, Comello held up his left hand to display the writings as the click and whirr of camera lenses filled the room with sound.

During the hearing, Comello did not speak other than to say, "Yes, sir" to the judge to respond to several procedural questions.

Cali, 53, was shot to death last Wednesday by a gunman who may have crashed his truck into Cali's car to lure him outside. Police said Cali was shot 10 times.

Federal prosecutors referred to Cali in court filings in 2014 as the underboss of the Mafia's Gambino family, once one of the country's most powerful crime organizations. News accounts since 2015 said Cali had ascended to the top spot, though he was never charged with leading the gang. His only mob-related conviction came a decade ago, when he was sentenced to 16 months in prison in an extortion scheme involving a failed attempt to build a NASCAR track on Staten Island. He was released in 2009 and hasn't been in legal trouble since then.

Police have not yet said whether they believe Cali's murder was a mob hit or whether he was killed for some other motive.

The last Mafia boss to be rubbed out in New York City was Gambino don "Big Paul" Castellano, who was assassinated in 1985.

Saturday, March 16, 2019

Anthony Comello Arrested in Murder of Frank Cali, Mafia Hit May Have Been Domestic Violence Beef Instead

The mafia didn’t kill Gambino boss Francesco “Franky Boy” Cali — a twentysomething Staten Island hothead with a personal beef did, police and sources said Saturday.

Anthony Comello , 24, a non-mobster who works odd construction jobs, was named as the suspect who blasted at least ten slugs into Cali, 53, on the street outside the boss’s brick mansion.

, 24, a non-mobster who works odd construction jobs, was named as the suspect who blasted at least ten slugs into Cali, 53, on the street outside the boss’s brick mansion.

It was the first assassination of a New York City mob boss since an upstart John Gotti had Gambino boss Paul Castellano whacked outside Sparks Steak House in 1985.

Investigators quickly feared a mob war in the making.But they now believe a personal dispute was to blame — over a woman in Cali’s family, according to multiple law enforcement sources.

The nature of the dispute was not immediately clear. But sources said Cali — who helmed a family notorious for gambling, loan sharking, and its deadly trade in heroin and oxycodone — thought Comello was trouble, sources said.

Cali didn’t think Comello was worthy of associating with a woman in his family, the sources added.

At a press conference Saturday afternoon, Chief of Detectives Dermot Shea announced Comello’s arrest, but said such issues as motive and possible accomplices were still under investigation.

“Everything is on the table at this point,” he said. “The investigation continues.”

Thanks to Larry Celona and Amanda Woods.

Anthony Comello

, 24, a non-mobster who works odd construction jobs, was named as the suspect who blasted at least ten slugs into Cali, 53, on the street outside the boss’s brick mansion.

, 24, a non-mobster who works odd construction jobs, was named as the suspect who blasted at least ten slugs into Cali, 53, on the street outside the boss’s brick mansion.

It was the first assassination of a New York City mob boss since an upstart John Gotti had Gambino boss Paul Castellano whacked outside Sparks Steak House in 1985.

Investigators quickly feared a mob war in the making.But they now believe a personal dispute was to blame — over a woman in Cali’s family, according to multiple law enforcement sources.

The nature of the dispute was not immediately clear. But sources said Cali — who helmed a family notorious for gambling, loan sharking, and its deadly trade in heroin and oxycodone — thought Comello was trouble, sources said.

Cali didn’t think Comello was worthy of associating with a woman in his family, the sources added.

At a press conference Saturday afternoon, Chief of Detectives Dermot Shea announced Comello’s arrest, but said such issues as motive and possible accomplices were still under investigation.

“Everything is on the table at this point,” he said. “The investigation continues.”

Thanks to Larry Celona and Amanda Woods.

Potential Hit Man in Police Custody in the Shooting of Frank Cali, Reputed Godfather of the Gambino Crime Family #Breaking

New York City detectives have a 24-year-old man in custody related to the shooting death this week of reputed crime boss Francesco "Franky Boy" Cali.

"The investigation is still in progress and an arrest has not yet been made," NYPD Assistant Chief Patrick Conry wrote in an email.

Conry said the 24-year-old was taken into custody early Saturday, but he did not say where. More information is expected to be released Saturday afternoon.

Citing "sources familiar with the investigation," NBC 4 New York reported the 24-year-old was arrested in Brick, New Jersey.

Cali, 53, died at a hospital after being shot multiple times in the torso in front of his home at 25 Hilltop Terrace in Staten Island. Police found Cali wounded after receiving a 911 call reporting an assault in progress about 9:15 p.m. Wednesday.

Federal prosecutors have referred to Cali in court filings as the underboss of the Gambino family, saying he was connected through marriage to the Inzerillo clan in the Sicilian Mafia.

Multiple press accounts since 2015 said Cali had ascended to the top spot in the gang, although he never faced a criminal charge saying so.

His death marks the first killing of a New York City boss in more than 30 years, according to reports. Former Gambino head Paul Castellano was famously killed in 1985 outside a midtown Manhattan steakhouse in a hit ordered by John Gotti, who seized control of the family.

"The investigation is still in progress and an arrest has not yet been made," NYPD Assistant Chief Patrick Conry wrote in an email.

Conry said the 24-year-old was taken into custody early Saturday, but he did not say where. More information is expected to be released Saturday afternoon.

Citing "sources familiar with the investigation," NBC 4 New York reported the 24-year-old was arrested in Brick, New Jersey.

Cali, 53, died at a hospital after being shot multiple times in the torso in front of his home at 25 Hilltop Terrace in Staten Island. Police found Cali wounded after receiving a 911 call reporting an assault in progress about 9:15 p.m. Wednesday.

Federal prosecutors have referred to Cali in court filings as the underboss of the Gambino family, saying he was connected through marriage to the Inzerillo clan in the Sicilian Mafia.

Multiple press accounts since 2015 said Cali had ascended to the top spot in the gang, although he never faced a criminal charge saying so.

His death marks the first killing of a New York City boss in more than 30 years, according to reports. Former Gambino head Paul Castellano was famously killed in 1985 outside a midtown Manhattan steakhouse in a hit ordered by John Gotti, who seized control of the family.

Friday, March 15, 2019

Frank Cali, Reputed Gambino Crime Boss, Shook Hands with Mafia Hit Man before Getting Whacked

Details continue to emerge as the investigation advances in the murder of a reputed Gambino family mob boss outside his Staten Island home, the first such incident in New York in three decades.

Multiple police sources say that whoever shot Francesco "Frankie Boy" Cali drove up to the mobster's Hilltop Terrace home in the Todt Hill section, came to a stop, and then gunned the engine in reverse, crashing into Cali's parked Cadillac SUV.

The force of the impact knocked the license plate off the SUV and seemed to investigators to have been done intentionally in order to get Cali's attention.

Once Cali came outside the home, sources said, video showed the two men talking and then shaking hands. Apparently Cali sensed no danger, because he turned his back on his killer to put the license plate inside the rear of the SUV.

That's when the gunman took out a 9mm handgun, held it with two hands -- as if he was trained, the sources said -- and opened fire.

The video is said to be grainy and has not been released because the suspect's face cannot be seen. The NYPD is continuing to canvass the neighborhood in search of clearer video.

Cali's wife and child were in the home at the time, which sources say is a highly unusual circumstance in the lore of organized crime -- which, in its heyday, followed certain rules that kept targets from getting whacked in front of their families.

Eyewitness News obtained Cali's mugshot from 2008, when he pleaded guilty in an extortion scheme involving a failed attempt to build a NASCAR track on Staten Island. He was sentenced to 16 months behind bars and was released in 2009. It is believed he took the reins of the notorious Gambino crime family in 2015.

Mob experts have been wary about possible conflicts erupting in the crime family, particularly after the brother of former Gambino boss John Gotti recently was released from prison. Gene Gotti is a reputed captain.

They say the type of hit -- at his home, with no real attempt to hide what happened -- suggests that it was a message killing. The question for detectives is what type of message was being sent.

This is the first time a reputed mob boss has been killed in New York City in more than 30 years.

The last Mafia boss to be shot to death in New York City was Gambino don Paul Castellano, assassinated outside a Manhattan steakhouse in 1985 at the direction of Gotti, who then took over.

Cali kept a much lower profile than Gotti.

With his expensive double-breasted suits and overcoats and silvery swept-back hair, Gotti became known as the Dapper Don, his smiling face all over the tabloids. As prosecutors tried and failed to bring him down, he came to be called the Teflon Don.

In 1992, Gotti was convicted in Castellano's murder and a multitude of other crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison and died of cancer in 2002.

Multiple police sources say that whoever shot Francesco "Frankie Boy" Cali drove up to the mobster's Hilltop Terrace home in the Todt Hill section, came to a stop, and then gunned the engine in reverse, crashing into Cali's parked Cadillac SUV.

The force of the impact knocked the license plate off the SUV and seemed to investigators to have been done intentionally in order to get Cali's attention.

Once Cali came outside the home, sources said, video showed the two men talking and then shaking hands. Apparently Cali sensed no danger, because he turned his back on his killer to put the license plate inside the rear of the SUV.

That's when the gunman took out a 9mm handgun, held it with two hands -- as if he was trained, the sources said -- and opened fire.

The video is said to be grainy and has not been released because the suspect's face cannot be seen. The NYPD is continuing to canvass the neighborhood in search of clearer video.

Cali's wife and child were in the home at the time, which sources say is a highly unusual circumstance in the lore of organized crime -- which, in its heyday, followed certain rules that kept targets from getting whacked in front of their families.

Eyewitness News obtained Cali's mugshot from 2008, when he pleaded guilty in an extortion scheme involving a failed attempt to build a NASCAR track on Staten Island. He was sentenced to 16 months behind bars and was released in 2009. It is believed he took the reins of the notorious Gambino crime family in 2015.

Mob experts have been wary about possible conflicts erupting in the crime family, particularly after the brother of former Gambino boss John Gotti recently was released from prison. Gene Gotti is a reputed captain.

They say the type of hit -- at his home, with no real attempt to hide what happened -- suggests that it was a message killing. The question for detectives is what type of message was being sent.

This is the first time a reputed mob boss has been killed in New York City in more than 30 years.

The last Mafia boss to be shot to death in New York City was Gambino don Paul Castellano, assassinated outside a Manhattan steakhouse in 1985 at the direction of Gotti, who then took over.

Cali kept a much lower profile than Gotti.

With his expensive double-breasted suits and overcoats and silvery swept-back hair, Gotti became known as the Dapper Don, his smiling face all over the tabloids. As prosecutors tried and failed to bring him down, he came to be called the Teflon Don.

In 1992, Gotti was convicted in Castellano's murder and a multitude of other crimes. He was sentenced to life in prison and died of cancer in 2002.

Thursday, March 14, 2019

Francesco "Frank" Cali, Reputed Gambino Crime Family Boss, Shot to Death Outside His Home

A reputed New York crime boss was shot and killed outside his home Wednesday night.

Francesco "Frank" Cali, 53, was found with multiple gunshot wounds to the torso in the borough of Staten Island, the NYPD said.

A law enforcement official confirmed that Cali was a high-ranking member of the Gambino organized crime family and is believed to be the acting boss.

Police are searching for a pickup truck that fled the scene, NY Police Chief of Detectives Dermot F. Shea said. No one has been arrested and the investigation is ongoing.

Cali was home with family members when the truck hit a car outside the residence, Shea said. It's "quite possible" that the incident was staged to draw Cali outside and into a confrontation with the suspected shooter, he said.

About a minute into the confrontation, the suspect pulled out a gun and began shooting at Cali, Shea said. When Cali tried to take cover behind his car, the pickup truck drove into it and "rocked" it significantly, possibly damaging the truck, Shea said.

Medics arrived at the scene and transported Cali to Staten Island University Hospital North, where he was pronounced dead.

Cali had been considered a unifying figure in the years after then-Gambino boss John Gotti, "Dapper Don," was convicted of murder and racketeering in 1992 and sent to prison for life. Unlike the well-dressed Gotti, Cali kept a low profile.

Cali was the first New York crime family boss shot in 34 years, according to WPIX. In 1985, Paul Castellano was shot dead as he arrived at Sparks Steakhouse in Manhattan -- a killing organized by Gotti, authorities said. Gotti, who then assumed control of the family, reportedly watched the action from nearby with his eventual underboss, Sammy "Bull" Gravano. But Gravano would eventually testify against Gotti, leading to Gotti's 1992 conviction in five murders -- one of several major convictions that thinned the Mafia ranks in the 1980s and '90s.

Cali was an associate in the Gambino family, according to court documents, when he was indicted in 2008 with more than two dozen other Gambino members for a range of alleged crimes.

Later that year, he pleaded guilty to extortion conspiracy related to the planned construction of a NASCAR speedway on Staten Island -- a plan that eventually was scrapped.

Authorities alleged Cali and others arranged, through force and threat of force, to receive cash payments from someone who had worked on the project.

Cali was sentenced to 16 months in prison and was released in 2009.

Francesco "Frank" Cali, 53, was found with multiple gunshot wounds to the torso in the borough of Staten Island, the NYPD said.

A law enforcement official confirmed that Cali was a high-ranking member of the Gambino organized crime family and is believed to be the acting boss.

Police are searching for a pickup truck that fled the scene, NY Police Chief of Detectives Dermot F. Shea said. No one has been arrested and the investigation is ongoing.

Cali was home with family members when the truck hit a car outside the residence, Shea said. It's "quite possible" that the incident was staged to draw Cali outside and into a confrontation with the suspected shooter, he said.

About a minute into the confrontation, the suspect pulled out a gun and began shooting at Cali, Shea said. When Cali tried to take cover behind his car, the pickup truck drove into it and "rocked" it significantly, possibly damaging the truck, Shea said.

Medics arrived at the scene and transported Cali to Staten Island University Hospital North, where he was pronounced dead.

Cali had been considered a unifying figure in the years after then-Gambino boss John Gotti, "Dapper Don," was convicted of murder and racketeering in 1992 and sent to prison for life. Unlike the well-dressed Gotti, Cali kept a low profile.

Cali was the first New York crime family boss shot in 34 years, according to WPIX. In 1985, Paul Castellano was shot dead as he arrived at Sparks Steakhouse in Manhattan -- a killing organized by Gotti, authorities said. Gotti, who then assumed control of the family, reportedly watched the action from nearby with his eventual underboss, Sammy "Bull" Gravano. But Gravano would eventually testify against Gotti, leading to Gotti's 1992 conviction in five murders -- one of several major convictions that thinned the Mafia ranks in the 1980s and '90s.

Cali was an associate in the Gambino family, according to court documents, when he was indicted in 2008 with more than two dozen other Gambino members for a range of alleged crimes.

Later that year, he pleaded guilty to extortion conspiracy related to the planned construction of a NASCAR speedway on Staten Island -- a plan that eventually was scrapped.

Authorities alleged Cali and others arranged, through force and threat of force, to receive cash payments from someone who had worked on the project.

Cali was sentenced to 16 months in prison and was released in 2009.

Tuesday, March 05, 2019

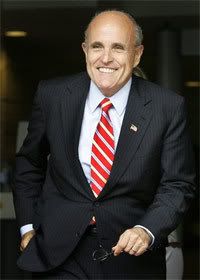

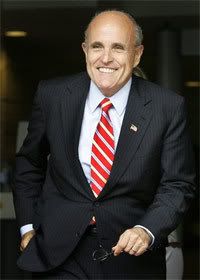

Mob Hit on Rudy Giuilani Discussed

The bosses of New York's five Cosa Nostra families discussed killing then-federal prosecutor Rudy Giuliani  in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

"The Bosses of the Luchese, Bonanno and Genovese families rejected the idea, despite strong efforts to convince them otherwise by Gotti and Persico," said an FBI report of the information given by informant Gregory Scarpa Sr.

Information about the purported murder plot was given to the FBI in 1987 by Scarpa, a Colombo captain, according to the testimony of FBI agent William Bolinder in State Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

Bolinder was testifying as a prosecution witness in the murder trial of ex-FBI agent Roy Lindley DeVecchio, who handled the now deceased Scarpa for years while the mobster was a key informant. Prosecutors contend that DeVecchio passed information to Scarpa that the mobster used in killings.

In his testimony, Bolinder described the contents of a voluminous FBI file on Scarpa, who died of AIDS in 1994.

In September 1987, DeVecchio reported that Scarpa told him that the five mob families talked about killing Giuliani approximately a year earlier, said Bolinder. It was in September 1986 that Giuliani's staff at the Manhattan U.S. attorney's office prosecuted bosses of La Cosa Nostra families in the so-called "Commission" case.

The Commission trial, a springboard for Giuliani's reputation as a crime buster, resulted in the conviction in October 1986 of Colombo boss Carmine Persico, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo and Genovese street boss Anthony Salerno. Gambino boss Paul Castellano was assassinated in December 1985 and the case against Bonanno boss Philip Rastelli was dropped.

The purported discussion about murdering Giuliani wasn't the first time he was targeted. In an interview in 1985 Giuliani stated that Albanian drug dealers plotted to kill him and two other officials. A murder contract price of $400,000 was allegedly offered by convicted heroin dealer Zhevedet Lika for the deaths of prosecutor Alan Cohen and DEA agent Jack Delmore, said Giuliani. Neither Cohen nor Delmore were harmed.

Other tidbits offered by Scarpa to DeVecchio involved an allegation of law enforcement corruption within the Brooklyn district attorney's office, said Bolinder. In 1983, stated Bolinder, Scarpa reported that an NYPD detective assigned to the Brooklyn district attorney's office (then led by Elizabeth Holtzman) had been taking money to leak information to the Gambino and Colombo families. A spokesman for current Brooklyn District Attorney Charles J. Hynes said no investigation was ever done about the allegation.

Scarpa also reported to DeVecchio that top Colombo crime bosses suspected the Casa Storta restaurant in Brooklyn was bugged because FBI agents never surveilled the mobsters when they met there. The restaurant was in fact bugged, government records showed.

Thanks to Anthony M. Destefano

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony."The Bosses of the Luchese, Bonanno and Genovese families rejected the idea, despite strong efforts to convince them otherwise by Gotti and Persico," said an FBI report of the information given by informant Gregory Scarpa Sr.

Information about the purported murder plot was given to the FBI in 1987 by Scarpa, a Colombo captain, according to the testimony of FBI agent William Bolinder in State Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

Bolinder was testifying as a prosecution witness in the murder trial of ex-FBI agent Roy Lindley DeVecchio, who handled the now deceased Scarpa for years while the mobster was a key informant. Prosecutors contend that DeVecchio passed information to Scarpa that the mobster used in killings.

In his testimony, Bolinder described the contents of a voluminous FBI file on Scarpa, who died of AIDS in 1994.

In September 1987, DeVecchio reported that Scarpa told him that the five mob families talked about killing Giuliani approximately a year earlier, said Bolinder. It was in September 1986 that Giuliani's staff at the Manhattan U.S. attorney's office prosecuted bosses of La Cosa Nostra families in the so-called "Commission" case.

The Commission trial, a springboard for Giuliani's reputation as a crime buster, resulted in the conviction in October 1986 of Colombo boss Carmine Persico, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo and Genovese street boss Anthony Salerno. Gambino boss Paul Castellano was assassinated in December 1985 and the case against Bonanno boss Philip Rastelli was dropped.

The purported discussion about murdering Giuliani wasn't the first time he was targeted. In an interview in 1985 Giuliani stated that Albanian drug dealers plotted to kill him and two other officials. A murder contract price of $400,000 was allegedly offered by convicted heroin dealer Zhevedet Lika for the deaths of prosecutor Alan Cohen and DEA agent Jack Delmore, said Giuliani. Neither Cohen nor Delmore were harmed.

Other tidbits offered by Scarpa to DeVecchio involved an allegation of law enforcement corruption within the Brooklyn district attorney's office, said Bolinder. In 1983, stated Bolinder, Scarpa reported that an NYPD detective assigned to the Brooklyn district attorney's office (then led by Elizabeth Holtzman) had been taking money to leak information to the Gambino and Colombo families. A spokesman for current Brooklyn District Attorney Charles J. Hynes said no investigation was ever done about the allegation.

Scarpa also reported to DeVecchio that top Colombo crime bosses suspected the Casa Storta restaurant in Brooklyn was bugged because FBI agents never surveilled the mobsters when they met there. The restaurant was in fact bugged, government records showed.

Thanks to Anthony M. Destefano

Related Headlines

Anthony Corallo,

Carmine Persico,

Greg Scarpa Sr.,

John Gotti,

Lin DeVecchio,

Paul Castellano,

Philip Rastelli,

Rudy Giuliani,

Tony Salerno

1 comment:

Wednesday, September 05, 2018

Gene Gotti, Brother of Mafia Godfather John Gotti, to Be Released from Prison

If the late John Gotti’s long-jailed brother finds the 21st-century Mafia unrecognizable later this month, he knows where the blame lies.

Gene Gotti , behind bars since 1989 for running a multi-million dollar heroin distribution ring, is set for a Sept. 15 release from the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, La. The Long Island father of three, now 71, wore a white jogging suit and cracked wise about his upcoming prison time when surrendering in the last millennium at the Brooklyn Federal Courthouse.

, behind bars since 1989 for running a multi-million dollar heroin distribution ring, is set for a Sept. 15 release from the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, La. The Long Island father of three, now 71, wore a white jogging suit and cracked wise about his upcoming prison time when surrendering in the last millennium at the Brooklyn Federal Courthouse.

Back in the ’80s heyday of his immaculately-dressed older brother and the Gambino family, FBI bugs captured Gene discussing topics from drug dealing to hiding illegal cash to changes in mob hierarchy.

The recordings of the Gambino capo and his mob associates became the first damaging domino to fall for the family in 1983, setting in motion the demise of their criminal empire.

What remains is a faint whisper of the roar that followed the ascension to boss of John (Dapper Don) Gotti, who took over after ordering the Dec. 16, 1985, mob assassination of predecessor “Big Paul” Castellano — in part to save his smack-dealing sibling’s life.

“What is Genie coming home to?” mused one long-retired Gambino family hand and Gotti contemporary. “There’s nothing left.”

When Gene Gotti started his 50-year prison bid, George H.W. Bush was in year one at the White House, an earthquake rocked the Bay Area World Series and the lip-syncing duo Milli Vanilli topped the charts.

Gene Gotti was convicted at his third federal drug-dealing trial, with jury tampering cited for a mistrial in the first one and a hung jury in the second. He and brother John were also cleared in a 1987 federal racketeering case where a juror was bribed.

Angel Gotti, Gene’s niece and the daughter of John, expects her uncle to find his footing in freedom.

“My uncle has been away 29 years so I'm sure he will be spending all his time with his wife, kids and grandchildren,” Angel told the Daily News.

Gene became one of five Gotti brothers to embrace “The Life” of organized crime. Though John emerged as the top gun, Gene earned his own spurs and became a valued mobster.

“He was a bona-fide wiseguy,” said ex-FBI agent Bruce Mouw, former head of the agency’s Gambino squad. “He wasn’t there because of his brother. He made it on his own.” But bona fide wiseguys are hard to find in 2018. Big brother John is dead 16 years, and sibling Peter appears destined to die behind bars, too. John’s namesake son Junior Gotti quit the mob after doing time for a strip club shakedown; he then survived four prosecutions that ended in mistrials. The Gotti crew’s Bergin Hunt & Fish Club in Ozone Park, Queens, is gone, replaced by the Lords of Stitch and Print custom embroidery shop.

Even the Mafia “brand” is down: The recently-released movie with John Travolta playing the “Teflon Don” grossed a mere $4.3 million — hardly “Godfather” numbers.

“The American Mafia has a recruitment problem: Who the hell wants to be a member?” said mob expert Howard Abadinsky, professor of criminal justice at St. John’s.

The new generation is filled with wanna-bes “who have either seen too many Mafia movies or losers who do not have the smarts or ambition for legitimate opportunity,” he added.

The older generation was not always a Mensa meeting, either — and Gene Gotti was Example A.

By the early 1980s, Gene was partnered with pals John Carneglia and Angelo Ruggiero in a lucrative heroin operation that ignored a Mafia edict against dope dealing. Gambino boss Castellano imposed a death penalty for violators, worried that drug convictions with lengthy jail terms provided an incentive for mobsters to rat out the family’s top echelon.

Gotti and his cohorts not only ignored the decree, they were caught discussing their drug dealing on an FBI bug planted in Ruggiero’s home. “Dial any seven numbers and it's 50/50 Angelo will pick up the phone,” a disgusted Carneglia later observed of his chatty cohort.

For Mouw, the recordings that led to Gene Gotti’s August 1983 arrest altered the landscape for the feds and the felons under their watch. “Without those conversations, a lot of things could have changed,” he said.

Instead, Castellano was soon pressing the Gotti faction for the damning tapes turned over by prosecutors as part of pre-trial discovery. The boss’ demand was greeted with excuses and delays, until Castellano was whacked 10 days before Christmas outside a Midtown steakhouse.

Decades later, it’s too late to change anything — including Gene’s decision to reject a plea deal that might have freed him after just seven years in prison.

“His brother John said no,” recalled Mouw. “He and Carneglia, they would have been home 20 years ago.”

The past is the past. What does the future hold for Gene Gotti?

“That’s the big question,” said Mouw. “Are you going to retire and enjoy your grandchildren? Or are you going to get active, and return to jail?"

Thanks to Larry McShane.

Gene Gotti

, behind bars since 1989 for running a multi-million dollar heroin distribution ring, is set for a Sept. 15 release from the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, La. The Long Island father of three, now 71, wore a white jogging suit and cracked wise about his upcoming prison time when surrendering in the last millennium at the Brooklyn Federal Courthouse.

, behind bars since 1989 for running a multi-million dollar heroin distribution ring, is set for a Sept. 15 release from the Federal Correctional Institution in Pollock, La. The Long Island father of three, now 71, wore a white jogging suit and cracked wise about his upcoming prison time when surrendering in the last millennium at the Brooklyn Federal Courthouse.Back in the ’80s heyday of his immaculately-dressed older brother and the Gambino family, FBI bugs captured Gene discussing topics from drug dealing to hiding illegal cash to changes in mob hierarchy.

The recordings of the Gambino capo and his mob associates became the first damaging domino to fall for the family in 1983, setting in motion the demise of their criminal empire.

What remains is a faint whisper of the roar that followed the ascension to boss of John (Dapper Don) Gotti, who took over after ordering the Dec. 16, 1985, mob assassination of predecessor “Big Paul” Castellano — in part to save his smack-dealing sibling’s life.

“What is Genie coming home to?” mused one long-retired Gambino family hand and Gotti contemporary. “There’s nothing left.”

When Gene Gotti started his 50-year prison bid, George H.W. Bush was in year one at the White House, an earthquake rocked the Bay Area World Series and the lip-syncing duo Milli Vanilli topped the charts.

Gene Gotti was convicted at his third federal drug-dealing trial, with jury tampering cited for a mistrial in the first one and a hung jury in the second. He and brother John were also cleared in a 1987 federal racketeering case where a juror was bribed.

Angel Gotti, Gene’s niece and the daughter of John, expects her uncle to find his footing in freedom.

“My uncle has been away 29 years so I'm sure he will be spending all his time with his wife, kids and grandchildren,” Angel told the Daily News.

Gene became one of five Gotti brothers to embrace “The Life” of organized crime. Though John emerged as the top gun, Gene earned his own spurs and became a valued mobster.

“He was a bona-fide wiseguy,” said ex-FBI agent Bruce Mouw, former head of the agency’s Gambino squad. “He wasn’t there because of his brother. He made it on his own.” But bona fide wiseguys are hard to find in 2018. Big brother John is dead 16 years, and sibling Peter appears destined to die behind bars, too. John’s namesake son Junior Gotti quit the mob after doing time for a strip club shakedown; he then survived four prosecutions that ended in mistrials. The Gotti crew’s Bergin Hunt & Fish Club in Ozone Park, Queens, is gone, replaced by the Lords of Stitch and Print custom embroidery shop.

Even the Mafia “brand” is down: The recently-released movie with John Travolta playing the “Teflon Don” grossed a mere $4.3 million — hardly “Godfather” numbers.

“The American Mafia has a recruitment problem: Who the hell wants to be a member?” said mob expert Howard Abadinsky, professor of criminal justice at St. John’s.

The new generation is filled with wanna-bes “who have either seen too many Mafia movies or losers who do not have the smarts or ambition for legitimate opportunity,” he added.

The older generation was not always a Mensa meeting, either — and Gene Gotti was Example A.

By the early 1980s, Gene was partnered with pals John Carneglia and Angelo Ruggiero in a lucrative heroin operation that ignored a Mafia edict against dope dealing. Gambino boss Castellano imposed a death penalty for violators, worried that drug convictions with lengthy jail terms provided an incentive for mobsters to rat out the family’s top echelon.

Gotti and his cohorts not only ignored the decree, they were caught discussing their drug dealing on an FBI bug planted in Ruggiero’s home. “Dial any seven numbers and it's 50/50 Angelo will pick up the phone,” a disgusted Carneglia later observed of his chatty cohort.

For Mouw, the recordings that led to Gene Gotti’s August 1983 arrest altered the landscape for the feds and the felons under their watch. “Without those conversations, a lot of things could have changed,” he said.

Instead, Castellano was soon pressing the Gotti faction for the damning tapes turned over by prosecutors as part of pre-trial discovery. The boss’ demand was greeted with excuses and delays, until Castellano was whacked 10 days before Christmas outside a Midtown steakhouse.

Decades later, it’s too late to change anything — including Gene’s decision to reject a plea deal that might have freed him after just seven years in prison.

“His brother John said no,” recalled Mouw. “He and Carneglia, they would have been home 20 years ago.”

The past is the past. What does the future hold for Gene Gotti?

“That’s the big question,” said Mouw. “Are you going to retire and enjoy your grandchildren? Or are you going to get active, and return to jail?"

Thanks to Larry McShane.

Related Headlines

Angelo Ruggiero,

Gene Gotti,

John Carneglia,

John Gotti,

Junior Gotti,

Paul Castellano

No comments:

Monday, July 09, 2018

Where the Mob Bodies, Bootleggers and Blackmailers are Buried in the Lurid History of Chicago’s Prohibition Gangsters

In 1981, an FBI team visited Donald Trump to discuss his plans for a casino in Atlantic City. Trump admitted to having ‘read in the press’ and ‘heard from acquaintances’ that the Mob ran Atlantic City. At the time, Trump’s acquaintances included his lawyer Roy Cohn, whose other clients included those charming New York businessmen Antony ‘Fat Tony’ Salerno and Paul ‘Big Paul’ Castellano.

‘I’ve known some tough cookies over the years,’ Trump boasted in 2016. ‘I’ve known the people that make the politicians you and I deal with every day look like little babies.’ No one minded too much. Organised crime is a tapeworm in the gut of American commerce, lodged since Prohibition. The Volstead Act of January 1920 raised the cost of a barrel of beer from $3.50 to $55. By 1927, the profits from organised crime were $500 million in Chicago alone. The production, distribution and retailing of alcohol was worth $200 million. Gambling brought in $167 million. Another $133 million came from labour racketeering, extortion and brothel-keeping.

In 1920 , Chicago’s underworld was divided between a South Side gang, led by the Italian immigrant ‘Big Jim’ Colosino, and the Irish and Jewish gangs on the North Side. Like many hands-on managers, Big Jim had trouble delegating, even when it came to minor tasks such as beating up nosy journalists. When the North Side gang moved into bootlegging, Colesino’s nephew John Torrio suggested that the South Side gang compete for a share of the profits. Colesino, fearing a turf war, refused. So Torrio murdered his uncle and started bootlegging.

, Chicago’s underworld was divided between a South Side gang, led by the Italian immigrant ‘Big Jim’ Colosino, and the Irish and Jewish gangs on the North Side. Like many hands-on managers, Big Jim had trouble delegating, even when it came to minor tasks such as beating up nosy journalists. When the North Side gang moved into bootlegging, Colesino’s nephew John Torrio suggested that the South Side gang compete for a share of the profits. Colesino, fearing a turf war, refused. So Torrio murdered his uncle and started bootlegging.

Torrio was a multi-ethnic employer. Americans consider this a virtue, even among murderers. The Italian ‘Roxy’ Vanilli and the Irishman ‘Chicken Harry’ Cullet rubbed along just fine with ‘Jew Kid’ Grabiner and Mike ‘The Greek’ Potson — until someone said hello to someone’s else’s little friend.

Torrio persuaded the North Side leader Dean O’Banion to agree to a ‘master plan’ for dividing Chicago. The peace held for four years. While Torrio opened an Italian restaurant featuring an operatic trio, ‘refined cabaret’ and ‘1,000,000 yards of spaghetti’, O’Banion bought some Thompson submachine guns. A racketeering cartel could not be run like a railroad cartel. There was no transparency among tax-dodgers, no trust between thieves, and no ‘enforcement device’ other than enforcement.

In May 1924, O’Banion framed Torrio for a murder and set him up for a brewery raid. In November 1924, Torrio’s gunmen killed O’Banion as he was clipping chrysanthemums in his flower shop. Two months later, the North Side gang ambushed Torrio outside his apartment and clipped him five times at close range.

Torrio survived, but he took the hint and retreated to Italy. His protégé Alphonse ‘Scarface’ Capone took over the Chicago Outfit. The euphemists of Silicon Valley would call Al Capone a serial disrupter who liked breaking things. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, there had been more than 700 Mob killings in Chicago alone.

On St Valentine’s Day 1929, Capone’s men machine-gunned seven North Siders in a parking garage. This negotiation established the Chicago Outfit’s supremacy in Chicago, and cleared the way for another Torrio scheme. In May 1929, Torrio invited the top Italian, Jewish and Irish gangsters to a hotel in Atlantic City and suggested they form a national ‘Syndicate’. The rest is violence.

Is crime just another American business, a career move for entrepreneurial immigrants in a hurry? John J. Binder teaches business at the University of Illinois in Chicago, and has a sideline in the Mob history racket. He knows where the bodies are buried, and by whom. We need no longer err by confusing North Side lieutenant Earl ‘Hymie’ Weiss, who shot his own brother in the chest, with the North Side ‘mad hatter’ Louis ‘Diamond Jack’ Allerie, who was shot in the back by his own brother; or with the bootlegger George Druggan who, shot in the back, told the police that it was a self-inflicted wound. Anyone who still mixes them up deserves a punishment beating from the American Historical Association.

Binder does his own spadework, too. Digging into Chicago’s police archives, folklore, and concrete foundations, he establishes that Chicago’s mobsters pioneered the drive-by shooting. As the unfortunate Willie Dickman discovered on 3 September 1925, they were also the first to use a Thompson submachine gun for a ‘gangland hit’. Yet the Scarface image of the Thompson-touting mobster was a fiction. Bootleggers preferred the shotgun and assassins the pistol. Thompsons were used ‘sparingly’, like a niblick in golf.

Al Capone’s Beer Wars is a well-researched source book. Readers who never learnt to read nothing because they was schooled on the mean streets will appreciate Binder’s data graphs and mugshots. Not too shabby for a wise guy.

Thanks to Dominic Green.

‘I’ve known some tough cookies over the years,’ Trump boasted in 2016. ‘I’ve known the people that make the politicians you and I deal with every day look like little babies.’ No one minded too much. Organised crime is a tapeworm in the gut of American commerce, lodged since Prohibition. The Volstead Act of January 1920 raised the cost of a barrel of beer from $3.50 to $55. By 1927, the profits from organised crime were $500 million in Chicago alone. The production, distribution and retailing of alcohol was worth $200 million. Gambling brought in $167 million. Another $133 million came from labour racketeering, extortion and brothel-keeping.

In 1920

, Chicago’s underworld was divided between a South Side gang, led by the Italian immigrant ‘Big Jim’ Colosino, and the Irish and Jewish gangs on the North Side. Like many hands-on managers, Big Jim had trouble delegating, even when it came to minor tasks such as beating up nosy journalists. When the North Side gang moved into bootlegging, Colesino’s nephew John Torrio suggested that the South Side gang compete for a share of the profits. Colesino, fearing a turf war, refused. So Torrio murdered his uncle and started bootlegging.

, Chicago’s underworld was divided between a South Side gang, led by the Italian immigrant ‘Big Jim’ Colosino, and the Irish and Jewish gangs on the North Side. Like many hands-on managers, Big Jim had trouble delegating, even when it came to minor tasks such as beating up nosy journalists. When the North Side gang moved into bootlegging, Colesino’s nephew John Torrio suggested that the South Side gang compete for a share of the profits. Colesino, fearing a turf war, refused. So Torrio murdered his uncle and started bootlegging.Torrio was a multi-ethnic employer. Americans consider this a virtue, even among murderers. The Italian ‘Roxy’ Vanilli and the Irishman ‘Chicken Harry’ Cullet rubbed along just fine with ‘Jew Kid’ Grabiner and Mike ‘The Greek’ Potson — until someone said hello to someone’s else’s little friend.

Torrio persuaded the North Side leader Dean O’Banion to agree to a ‘master plan’ for dividing Chicago. The peace held for four years. While Torrio opened an Italian restaurant featuring an operatic trio, ‘refined cabaret’ and ‘1,000,000 yards of spaghetti’, O’Banion bought some Thompson submachine guns. A racketeering cartel could not be run like a railroad cartel. There was no transparency among tax-dodgers, no trust between thieves, and no ‘enforcement device’ other than enforcement.

In May 1924, O’Banion framed Torrio for a murder and set him up for a brewery raid. In November 1924, Torrio’s gunmen killed O’Banion as he was clipping chrysanthemums in his flower shop. Two months later, the North Side gang ambushed Torrio outside his apartment and clipped him five times at close range.

Torrio survived, but he took the hint and retreated to Italy. His protégé Alphonse ‘Scarface’ Capone took over the Chicago Outfit. The euphemists of Silicon Valley would call Al Capone a serial disrupter who liked breaking things. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, there had been more than 700 Mob killings in Chicago alone.

On St Valentine’s Day 1929, Capone’s men machine-gunned seven North Siders in a parking garage. This negotiation established the Chicago Outfit’s supremacy in Chicago, and cleared the way for another Torrio scheme. In May 1929, Torrio invited the top Italian, Jewish and Irish gangsters to a hotel in Atlantic City and suggested they form a national ‘Syndicate’. The rest is violence.

Is crime just another American business, a career move for entrepreneurial immigrants in a hurry? John J. Binder teaches business at the University of Illinois in Chicago, and has a sideline in the Mob history racket. He knows where the bodies are buried, and by whom. We need no longer err by confusing North Side lieutenant Earl ‘Hymie’ Weiss, who shot his own brother in the chest, with the North Side ‘mad hatter’ Louis ‘Diamond Jack’ Allerie, who was shot in the back by his own brother; or with the bootlegger George Druggan who, shot in the back, told the police that it was a self-inflicted wound. Anyone who still mixes them up deserves a punishment beating from the American Historical Association.

Binder does his own spadework, too. Digging into Chicago’s police archives, folklore, and concrete foundations, he establishes that Chicago’s mobsters pioneered the drive-by shooting. As the unfortunate Willie Dickman discovered on 3 September 1925, they were also the first to use a Thompson submachine gun for a ‘gangland hit’. Yet the Scarface image of the Thompson-touting mobster was a fiction. Bootleggers preferred the shotgun and assassins the pistol. Thompsons were used ‘sparingly’, like a niblick in golf.

Al Capone’s Beer Wars is a well-researched source book. Readers who never learnt to read nothing because they was schooled on the mean streets will appreciate Binder’s data graphs and mugshots. Not too shabby for a wise guy.

Thanks to Dominic Green.

Related Headlines

Al Capone,

Big Jim Colosimo,

Books,

Dean O'Banion,

Donald Trump,

Earl Weiss,

Johnny Torrio,

Paul Castellano,

Roy Cohn,

Tony Salerno

No comments:

Tuesday, September 06, 2016

Reviewing the History of @RealDonaldTrump and The Mob

As billionaire developer Donald Trump became the toast of New York in the 1980s , he often attributed his rise to salesmanship and verve. "Deals are my art form," he wrote. But there is another aspect to his success that he doesn't often discuss. Throughout his early career, Trump routinely gave large campaign contributions to politicians who held sway over his projects and he worked with mob-controlled companies and unions to build them.

, he often attributed his rise to salesmanship and verve. "Deals are my art form," he wrote. But there is another aspect to his success that he doesn't often discuss. Throughout his early career, Trump routinely gave large campaign contributions to politicians who held sway over his projects and he worked with mob-controlled companies and unions to build them.

Americans have rarely contemplated a candidate quite like Trump, 69, who has become the unlikely leader among Republican Party contenders for the White House. He's a brash Queens-born scion who navigated through one of the most corrupt construction industries in the country to become a brand-name business mogul.

Much has been written about his early career, but many details have been obscured by the passage of time and overshadowed by Trump's success and celebrity.

A Washington Post review of court records, testimony by Trump and other accounts that have been out of the public eye for decades offer insights into his rise. He was never accused of illegality, and observers of the time say that working with the mob-related figures and politicos came with the territory. Trump declined repeated requests to comment.

One state examination in the late 1980s of the New York City construction industry concluded that "official corruption is part of an environment in which developers and contractors cultivate and seek favors from public officials at all levels."

Trump gave so generously to political campaigns that he sometimes lost track of the amounts, documents show. In 1985 alone, he contributed about $150,000 to local candidates, the equivalent of $330,000 today.

Officials with the New York State Organized Crime Task Force later said that Trump, while not breaking any laws, "circumvented" state limits on individual and corporate contributions "by spreading his payments among eighteen subsidiary companies."

Trump alluded to his history of political giving in August this year, at the first Republican debate, bragging that he gave money with the confidence that he would get something in return. "I was a businessman. I give to everybody. When they call, I give. And you know what? When I need something from them, two years later, three years later, I call them. They are there for me," he said. "And that's a broken system."

As he fed the political machine, he also had to work with unions and companies known to be controlled by New York's ruling mafia families, which had infiltrated the construction industry, according to court records, federal task force reports and newspaper accounts. No serious presidential candidate has ever had his depth of business relationships with the mob-controlled entities.

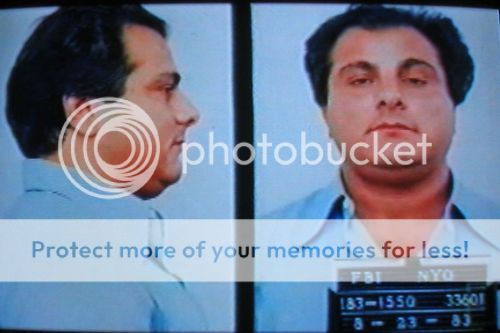

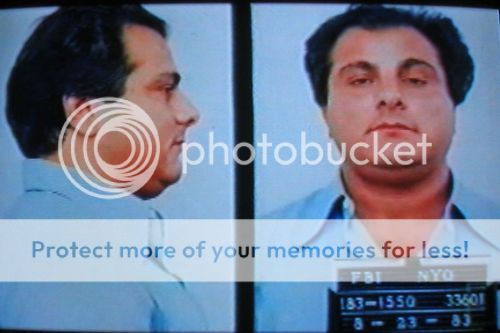

The companies included S & A Concrete Co., which supplied building material to the Trump Plaza on Manhattan's east side, court records show. S & A was owned by Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno, boss of the Genovese crime family, and Paul Castellano, boss of the Gambino family. The men required that major multimillion-dollar construction projects obtain concrete through S & A at inflated prices, according to a federal indictment of Salerno and others.

Salerno eventually went to prison on federal racketeering, bid-rigging and other charges. His attorney, Roy Cohn, the former chief counsel to Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.), was one of the most politically connected men in Manhattan. He was also Donald Trump's friend and occasionally his attorney. Cohn was never charged over any dealings with the mob, but he was disbarred shortly before his death in 1986 for ethical and financial improprieties.

"[T]he construction industry in New York City has learned to live comfortably with pervasive corruption and racketeering," according to "Corruption and Racketeering in the New York City Construction Industry," a 1990 report by the New York State Organized Crime Task Force. "Perhaps those with strong moral qualms were long ago driven from the industry; it would have been difficult for them to have survived. 'One has to go along to get along.' "

James B. Jacobs, the report's principal author, told The Post that Trump and other major developers at the time "had to adapt to that environment" or do business in another city. "That's not illegal, but you might say it's not a beautiful thing," said Jacobs, a law professor at New York University. "It was a very sick system."

Trump entered the real estate business full-time in 1968, following his graduation from The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He worked in Queens with his father, Fred Trump, who owned a development firm with apartment buildings and other holdings across the country. Donald, who had worked part-time for the firm for years, learned the business from the inside.

When he joined his father , Donald Trump examined the books and found tens of millions of untapped equity. Trump urged his father to take on more debt and expand the business in Manhattan. "At age twenty-two the young baron's dreams had already begun to assume the dimensions of an empire," Jerome Tuccille wrote in a biography of Trump.

, Donald Trump examined the books and found tens of millions of untapped equity. Trump urged his father to take on more debt and expand the business in Manhattan. "At age twenty-two the young baron's dreams had already begun to assume the dimensions of an empire," Jerome Tuccille wrote in a biography of Trump.

Donald Trump took over in 1971 and began cultivating the rich and powerful. He made regular donations to members of the city's Democratic machine. Mayors, borough presidents and other elected officials often were blunt in their requests for campaign cash and "loans," according to the commission on government integrity. Donald Trump later said that the richer he became, the more money he gave.

After a series of scandals not tied to Trump, campaign finance practices in the state came under scrutiny by the news media. In 1987, Gov. Mario Cuomo and New York Mayor Ed Koch appointed the state commission on government integrity and gave it subpoena power and a sweeping mandate to examine official corruption.

The commission created a database of state contribution records that previously had been kept haphazardly in paper files. It called on politicians and developers to explain the patterns of giving identified by the computer analysis.

Trump appeared one morning in March 1988, according to a transcript of his appearance obtained by The Post. He acknowledged that campaign contributions had been a routine part of his business for nearly two decades. He repeatedly told the commission he could not remember the details.

"In fact, in 1985 alone, your political contributions exceeded $150,000; is that correct?" Trump was asked. "I really don't know," he said. "I assume that is correct, yes."

A commission member said that Trump had made contributions through more than a dozen companies. "Why aren't these political contributions just made solely in your name?"

"Well, my attorneys basically said that this was the proper way of doing it," Trump said.

Trump told the commission that he also provided financial help to candidates in another way. In June 1985, he guaranteed a $50,000 loan for Andrew Stein, a Democrat who was running to be New York's City Council president. Six months later, Trump paid off the loan. "I was under the impression at the time it was made that I would be getting my money back," Trump told the commission. "And when were you disabused of that notion?" "When it was time to get my money back," Trump said.

Asked whether he considered such transactions as a "cost of doing business," Trump was equivocal. "I personally don't," he said. "But I can see that some people might very well feel that way, sir."

Stein told The Post he did not recall the loan, but he said developers were close to city officials at the time. "The Donald was a supporter, as well as a lot of the real estate people were," Stein said. "They have a huge interest in the city and have their needs."

Trump's donations were later cited by the organized crime task force's report as an example of the close financial relationships between developers and City Hall. "New York city real estate developers revealed how they were able to skirt the statutory proscriptions," the report said in a footnote. "Trump circumvented the State's $50,000 individual and $5,000 corporate contribution limits by spreading his payments among eighteen subsidiary companies."

Trump, then in his early 40s, said he made some donations to avoid hurting the feelings of friends, not to curry favor. "[Y]ou will have two or three friends running for the same office and they literally are all coming to you asking for help, and so it's a choice, give to nobody or give to everybody," according to his testimony at a 1988 hearing by the New York Commission on Government Integrity.

John Bienstock, the staff director of the Commission on Government Integrity at the time, recently told The Post that Trump took advantage of a loophole in the law. "They all did that," Bienstock said. "It inevitably leads to either the reality, or the perception, that approvals are being bought by political contributions."

As his ambitions expanded in the 1970s and 1980s, Trump had to contend with New York's Cosa Nostra in order to complete his projects. By the 1980s, crime families had a hand in all aspects of the contracting industry, including labor unions, government inspections, building supplies and trash carting.

"[O]rganized crime does not so much attack and subvert legitimate industry as exploit opportunities to work symbiotically with 'legitimate' industry so that 'everybody makes money,' " according to the organized crime task force report. "Organized crime and other labor racketeers have been entrenched in the building trades for decades."

In New York City, the mafia families ran what authorities called the "concrete club," a cartel of contractors that rigged bids and squelched competition from outsiders. They controlled the Cement and Concrete Workers union and used members to enforce their rules.

Nearly every major project in Manhattan during that period was built with mob involvement, according to court records and the organized crime task force report. That includes Trump Tower, the glittering 58-story skyscraper on Fifth Avenue, which was made of reinforced concrete.

"Using concrete , however, put Donald at the mercy of a legion of concrete racketeers," according to "Trump: The Deals and the Downfall" by investigative journalist Wayne Barrett.

, however, put Donald at the mercy of a legion of concrete racketeers," according to "Trump: The Deals and the Downfall" by investigative journalist Wayne Barrett.

For three years, the project's fate rested in part with the Teamsters Local 282, the members of which delivered the concrete. Leading the union was John Cody, who "was universally acknowledged to be the most significant labor racketeer preying on the construction industry in New York," according to documents cited by the House Subcommittee on Criminal Justice in 1989. Using his power to disrupt or shut down major projects, Cody extracted millions in "labor peace payoffs" from contractors, the documents said.

"Donald liked to deal with me through Roy Cohn," Cody said, according to Barrett.

Trump was subpoenaed by federal investigators in 1980 and asked to describe his relationship with Cody, who had allegedly promised to keep the project on track in exchange for an apartment in Trump Tower. Trump "emphatically denied" making such a trade, Barrett wrote.

Cody was later convicted on racketeering and tax-evasion charges.

The mob also played a role in the construction of Trump Plaza, the luxury apartment building on Manhattan's east side. The $7.8 million deal for concrete was reserved for S & A Concrete and its owners, court records show. The crime families did not advertise their role in S & A and the other contractors. But it was well known in the industry.

"They had to know about it," according to Jacobs, the lawyer who served on the organized crime task force. "Everybody knew about it."

While these building projects were underway in the early 1980s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and New York authorities carried out an unprecedented investigation of the five New York crime families. Investigators relied on informants, court-authorized wiretaps and eavesdropping gear. Over five years, they gathered hundreds of hours of conversations proving the mob's reach into the construction industry.

On Feb. 26, 1985, Salerno and 14 others were indicted on an array of criminal activity, including conspiracy, extortion and "infiltration of ostensibly legitimate businesses involved in selling ready-mix concrete in New York City," the federal indictment said. Among the projects cited was Trump Plaza. Salerno and all but one of the others received terms of 100 years in prison.